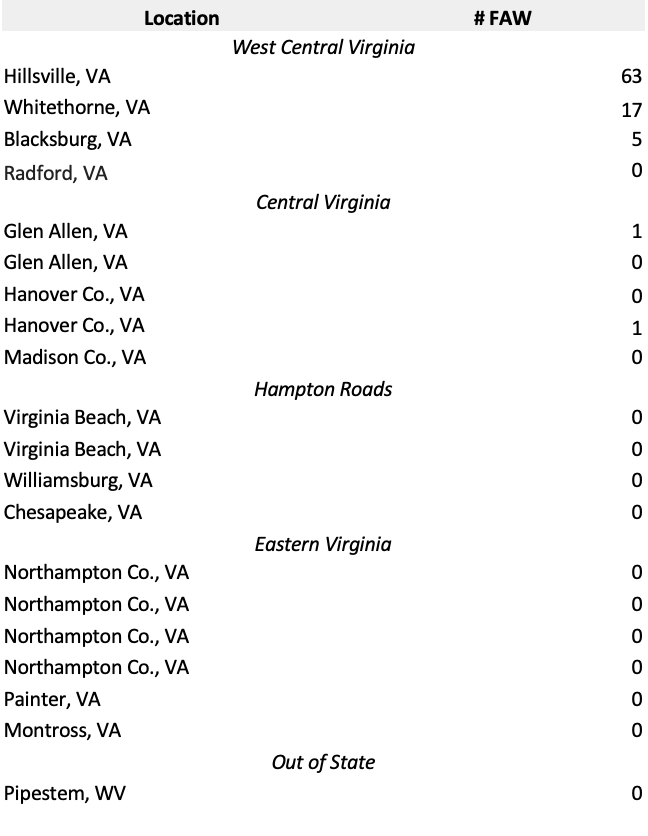

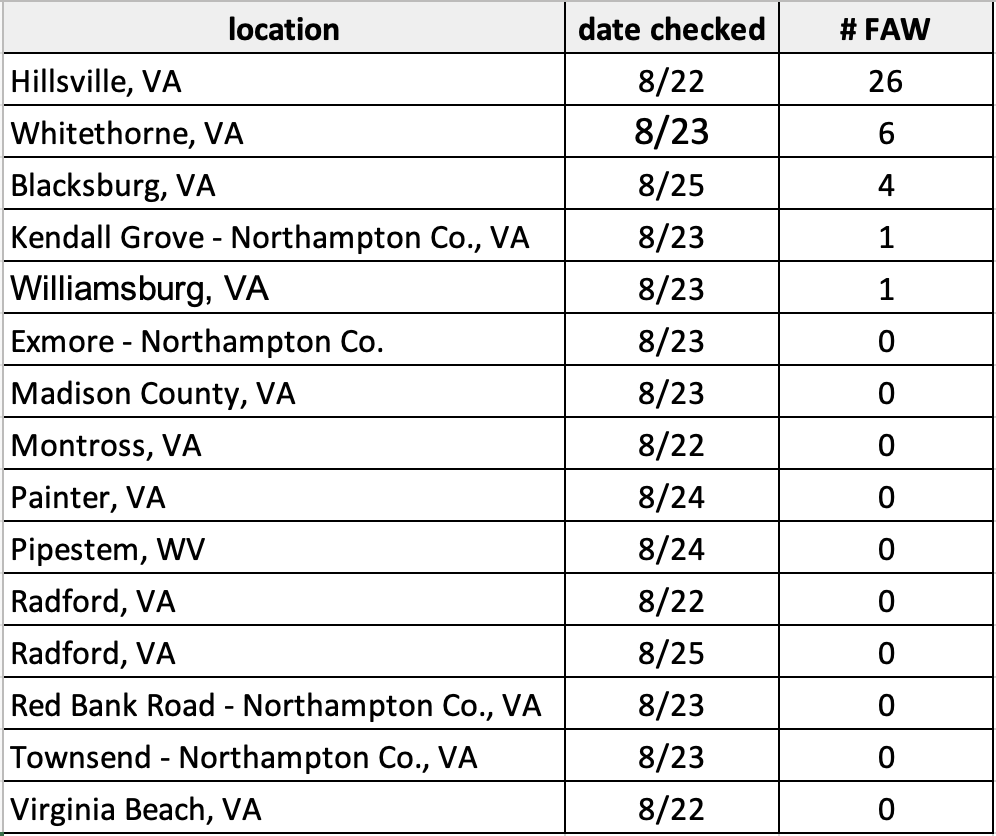

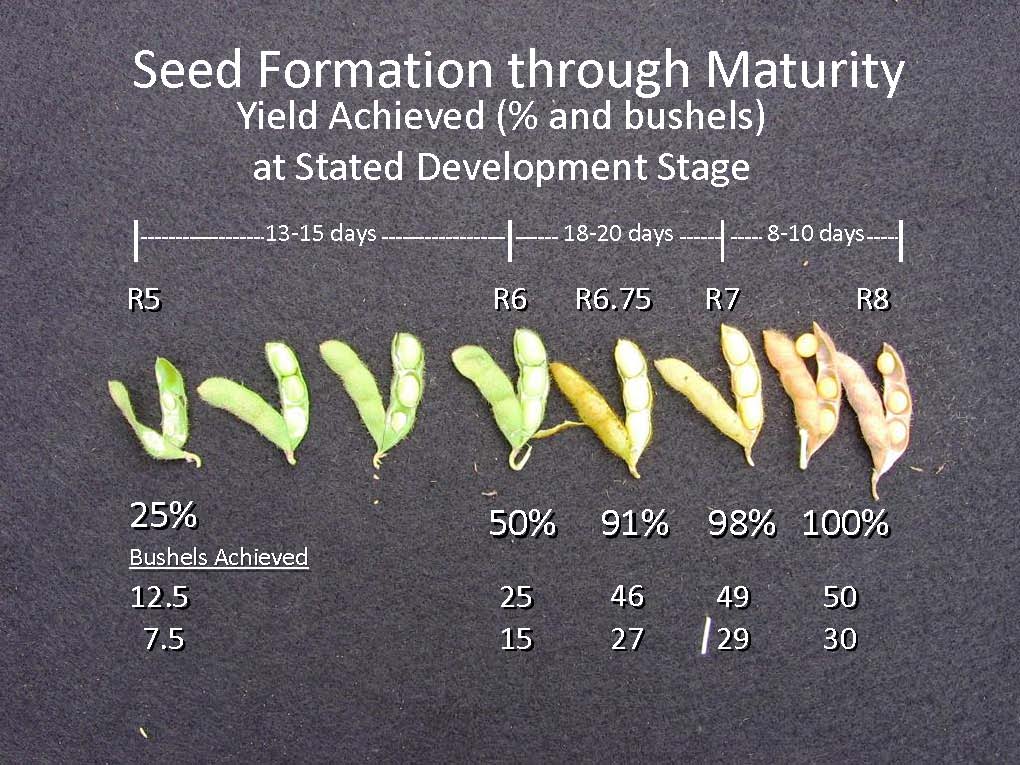

The soybean crop is rapidly moving along. Normally the R6 or late-seed filling stage will last about 3 weeks, although that time will shorten with late planting. Most of this year’s crop has reached that stage with the exception of late-maturing varieties planted double-crop after wheat harvest.

The crop has made only 50% of it’s yield at the beginning of this stage and about 75% of its yield 8 to 12 days into the stage. Only after the crop reaches physiological maturity is 95 to 100% of the yield been made. If stress such as we are having now occurs during this time, seed size will be small and some seed will abort in the pods.

The dry weather that we’ve recently experienced is speeding up development, aborting seed, and small seed size will likely occur. Areas that have received recent rainfall may not experience this. Unfortunately, yield may not be as good as they appear – the pod load will be deceiving in dry areas.

There are still some late-season decisions that need to be made in some parts, such aa harvest aid timing or late-season insecticide application.

So when can you apply a harvest aid to control weeds or possibly speed up development? First you need to follow the label. Different harvest aids have different requirements. Many are not allowed/legal until R7. If you however select a harvest aid that can be applied in the late-R6 stage, I suggest waiting until at least half of the leaves on the plant have dropped and half of those remaining are turning yellow. This is only within a few days until R7; about 15 days after beginning R6. Most of the yield should have been made by this time. Any application before this time could affect yield.

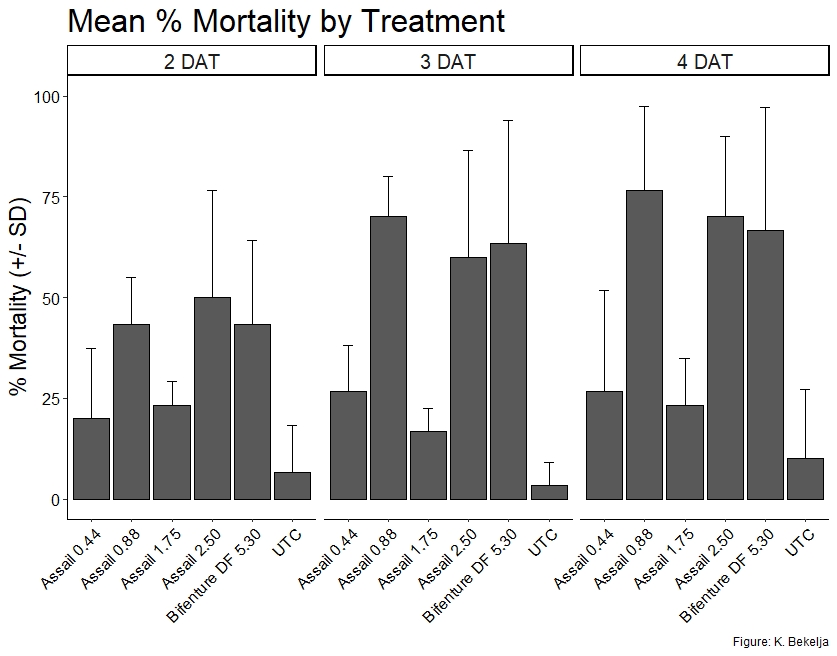

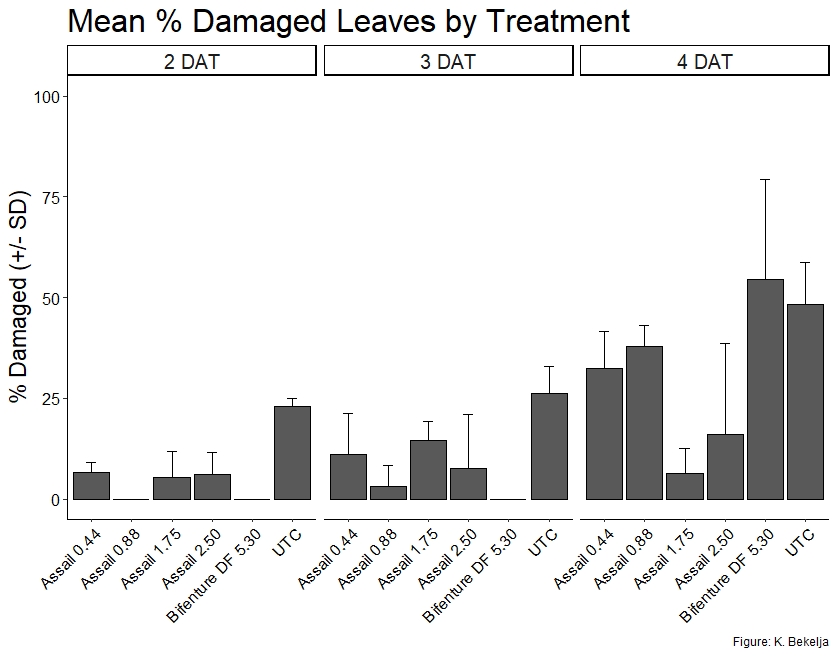

What if you are experiencing insect defoliation? Both Mexican bean beetle and soybean looper are causing some problems in different parts of Virginia. First, is it worth treating for defoliating pests at this late stage? If you have not entered the R6 stage and are still at R5, then severe defoliation (>15%; >10% for late-planted, poor growth) could greatly impact yield. But what if you are in the R6 stage? This will depend on 1) presence of the pest and how much defoliation you have experienced; 2) how long before you are at a “safe” stage, where you’ve reached most of your yield potential; and 3) the amount of leaf area – the more the better.

Our Pest Management Guide thresholds indicate that we can tolerate up to 35% defoliation for soybean that contains fully-developed seeds (with good growth/high leaf area; less for late-planted, poor growth). But we also need to consider how long before we reach R7. If you are half-way through R6, then you are probably “safe” and don’t need to spray, depending on how fast the defoliation is occurring and the number of pests present.

However, if your are only a few days into R6, the decision is much harder. As you can see from the above diagram, we’ve only made 50 to 75% of our yield by this time. With excess leaf area (we have this in many parts of Virginia this year), you can tolerate a good bit of defoliation, even at this stage. The real questions are how long before I reach the “safe” stage and how fast is the insect pest defoliating the crop. As I stated earlier, the dry weather is speeding up maturity; so, time to maturity could be reduced by several days. The crop could be getting less valuable with time. If this is the case, I would not expect a benefit of an insecticide application. But what if the crop is not under stress? As an agronomist, I lean towards protecting crop yield. But, these questions can only be answered on a field by field basis. And you’ll need all the information that you can get, from various sources.