David Holshouser, Extension Agronomist

Pat Phipps, Extension Plant Pathologist

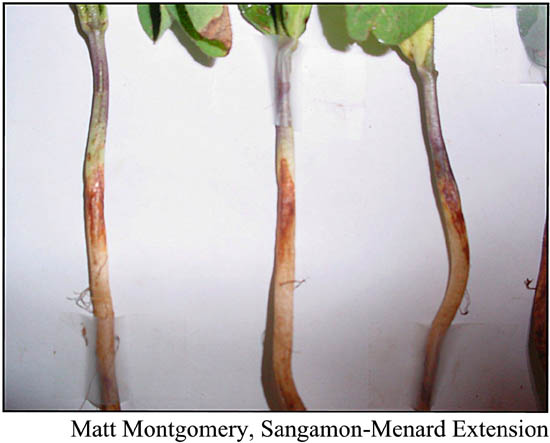

Rhizoctonia Damping Off and Root Rot. Rhizoctonia root rot is probably the most common soilborne disease in Virginia soybeans.  Even if other diseases pre-dominate in a diseased plant, rhizoctonia could easily be a component of the problem.

Even if other diseases pre-dominate in a diseased plant, rhizoctonia could easily be a component of the problem.

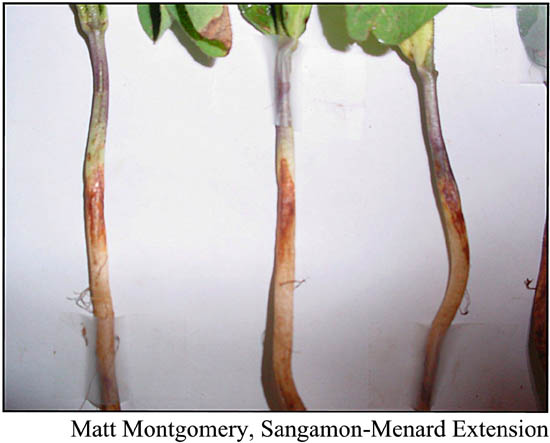

Preemergence symptoms are typical of common seed rots, but are not usually recognized just because these plants never emerge. More recognizable is the damping off that occurs in the seedling stage. This will usually occur before the first trifoliate leaf develops. Infected plants will have a reddish brown lesion on the emerged shoot at the soil line. This lesion is most visible after the seedling is removed from the soil.

Resistance to rhizoctonia is not available; variations in variety tolerance have been reported though. Stresses such as herbicide injury, poor soils, insect damage, and feeding by soybean cyst nematode will increase damage. Several fungicide seed treatments are effective for this disease.

Fusarium Root Rot. Fusarium is another common disease in Virginia. It is one of the diseases that has been implicated in “Essex Syndrome” that we continue to battle in some parts of Virginia. There are several species of fusarium and each can cause a different plant reaction and/or disease.

Two of the species, F. oxysporum and F. solani can cause root rot. The root rot caused by F. oxysporum usually develops on seedlings and young plants during cool weather (<60O soil temperatures). Older plants are generally less susceptible than younger ones. Seedlings will emerge very slow and the resulting seedlings are stunted and generally unhealthy. Symptoms are usually found confined to the roots and lower stems.

F. solani causes preemergence damping-off and root rot. Damping off after the seedlings emerge is less of a problem, but can occur. Lesions are generally on the roots and are dark brown to reddish brown to black. Lesions can also occur on the young stem.

This disease is common in nematode-infested fields. Soybean cyst, root knot, and sting nematodes will predispose seedlings. Soybeans growing in soybean cyst nematode-infested fields will frequently develop fusarium symptoms. This is less likely in root knot infested fields because the injury to the plant from root knot nematode is limited to the root tip. In contrast, larvae of soybean cyst nematode migrate within the cells and cause more wounding. In addition, F. oxysporum often interacts with rhizoctonia.

There is some variety resistance to the disease, but this information is not always published in the company literature. Warm soils that are well-drained are helpful in managing the disease. Good soil fertility should be maintained and soil compaction avoided. Fungicide seed treatments provide some, but limited control.

Pythium Damping-Off and Root Rot. There are many different species of pythium and the dominant species that is present will vary from geographical region to region, usually depending on temperature. Pythium will cause pre- and postemergence  damping-off during the young seedling stages. It can also cause a root rot in later vegetative stages. Seedlings may fail to emerge and will have a short, discolored root. After emergence, symptoms can resemble those of other seedling diseases, especially fusarium and phytophthora. The disease begins as water-soaked lesions on the young stem or on the cotyledons (seed leaves), and then followed by brown soft rot.

damping-off during the young seedling stages. It can also cause a root rot in later vegetative stages. Seedlings may fail to emerge and will have a short, discolored root. After emergence, symptoms can resemble those of other seedling diseases, especially fusarium and phytophthora. The disease begins as water-soaked lesions on the young stem or on the cotyledons (seed leaves), and then followed by brown soft rot.

Variety resistance to pythium is not available, but fungicide seed treatments containing metalaxyl or mefenoxam will control the disease. The best way to avoid the disease is to avoid planting into cool soils (<60oF).

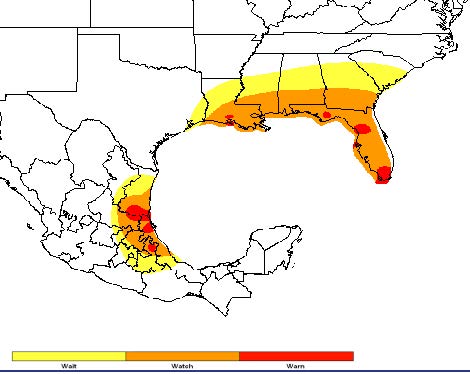

Phytophthora Root Rot. Of all the seedling disease that you may have heard about, phytophthora is probably the one that you hear and read about most. It is a serious problem in the Midwest and affects young seedlings and older plants.  Many of our varieties that we grow in Virginia have varying levels of resistance to multiple races of phytophthora. Yet, most of you have probably never had the disease. Why is that?

Many of our varieties that we grow in Virginia have varying levels of resistance to multiple races of phytophthora. Yet, most of you have probably never had the disease. Why is that?

Phytophthora rot is most severe in poorly drained clay soils that are readily flooded. Most of our soils are sandy in nature, or if a clay, are well-drained. This doesn’t mean you can’t have the problem just that it is less likely.  Plant loss can occur in lighter soils or on well-drained soils if they are saturated for an extended period of time when the plants are young.

Plant loss can occur in lighter soils or on well-drained soils if they are saturated for an extended period of time when the plants are young.

Symptoms are the typical root rot and pre- and postemergence damping off. The disease is often not diagnosed because it is confused with flooding damage. Root and stem rots occurring later in the season will occur under similar, saturated conditions. Tolerant cultivars may escape damage. Damage does increase with reduced tillage, especially no-till, mainly because those fields absorb more rainfall and can be more easily saturated if the field is poorly drained. Like most diseases, continuous soybean will increase likelihood of infection and damage.