Potato Leafhopper. This insect overwinters in gulf-coast states and migrates northward each year, typically arriving in Virginia between late April and early June. Adults and nymphs injure the plant by insertin g their piercing-sucking mouthparts into plant tissue and removing liquids. High populations can result in visual injury (cupping of leaves) and under drought conditions, can stunt growth, Injury is more severe on varieties with little leaf pubescence. But, the injury will not necessarily result in yield loss. Very dry conditions will increase injury and likelihood of yield loss. The insect can be controlled with pyrethroid insecticides.

g their piercing-sucking mouthparts into plant tissue and removing liquids. High populations can result in visual injury (cupping of leaves) and under drought conditions, can stunt growth, Injury is more severe on varieties with little leaf pubescence. But, the injury will not necessarily result in yield loss. Very dry conditions will increase injury and likelihood of yield loss. The insect can be controlled with pyrethroid insecticides.

Thrips may be the most abundant insect pest species on soybean. But, the feeding alone will not usually cause yield reduction. Under favorable environments, soybean will outgrow thrips damage. However, if high numbers of thrips coincide with droughty conditions early in the season (seedling plants), then growth can be severely  stunted and yield loss might occur. Thrips feed by rupturing the cell walls of leaf cells and sucking the exudates. Leaves will take on a silvery appearance from thrips feeding. The insect can be controlled with insecticides from several chemical classes. Early-season control can be obtained with insecticide seed treatments. Ames Herbert is updating thrips counts in cotton and other crops on a regular basis in his Virginia AG Pest Advisory found at http://www.sripmc.org/Virginia/.

stunted and yield loss might occur. Thrips feed by rupturing the cell walls of leaf cells and sucking the exudates. Leaves will take on a silvery appearance from thrips feeding. The insect can be controlled with insecticides from several chemical classes. Early-season control can be obtained with insecticide seed treatments. Ames Herbert is updating thrips counts in cotton and other crops on a regular basis in his Virginia AG Pest Advisory found at http://www.sripmc.org/Virginia/.

Bean leaf beetle is a common pest through all soybean production areas and has become more of a concern in the Midwest in recent years.  These beetles are defoliating insects, whose injury is easily recognized by small round holds between major leaflet veins. The insect can also feed on the surface of soybean pods, leaving the seed vulnerable to excess moisture and secondary pathogens. The insect can feed all year, but most concern is during the early vegetative stages. However, soybean can normally grow out of this injury, without yield loss. This insect can transmit the virus, bean pod mottle virus. However, viruses have not traditionally been a problem in soybean. There is resistance and/or tolerance in many varieties. However, we suspect that some newer varieties have less tolerance. The insect can be controlled with insecticides from several chemical classes.

These beetles are defoliating insects, whose injury is easily recognized by small round holds between major leaflet veins. The insect can also feed on the surface of soybean pods, leaving the seed vulnerable to excess moisture and secondary pathogens. The insect can feed all year, but most concern is during the early vegetative stages. However, soybean can normally grow out of this injury, without yield loss. This insect can transmit the virus, bean pod mottle virus. However, viruses have not traditionally been a problem in soybean. There is resistance and/or tolerance in many varieties. However, we suspect that some newer varieties have less tolerance. The insect can be controlled with insecticides from several chemical classes.

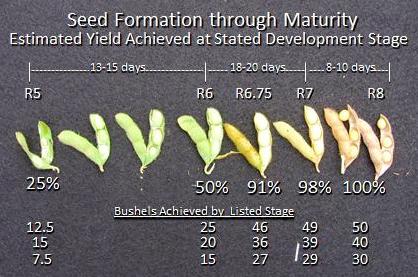

Soybean Aphid. Soybean aphid is a relatively new pest, first discovered in Virginia just 10 years ago. It feeds by sucking plant sap, which can cause leaf curling and plant stunting and pod abortion. At high levels, yield can be seriously reduced. While an early-season pest in the Great Lake states, it has never occurred in Virginia before July, and rarely before August. In addition, it only reaches threshold levels on relatively few acres in Virginia each year. We only mention this pest here because some companies are promoting early-season control of aphid with soil insecticides. Although soil insecticides may provide some control to seedling soybeans, this is not an issue in Virginia. Management of this pest depends on regular scouting and applying insecticides when threshold levels are reached (250 aphids/plant before R5).

it has never occurred in Virginia before July, and rarely before August. In addition, it only reaches threshold levels on relatively few acres in Virginia each year. We only mention this pest here because some companies are promoting early-season control of aphid with soil insecticides. Although soil insecticides may provide some control to seedling soybeans, this is not an issue in Virginia. Management of this pest depends on regular scouting and applying insecticides when threshold levels are reached (250 aphids/plant before R5).

White Grubs. With less tillage  and more residue buildup on our soils, grubs have become more of a concern. White grub damages soybean by feeding on soybean roots, killing young plants, and reducing stands. Insecticide seed treatments have some, but limited effect on grub.

and more residue buildup on our soils, grubs have become more of a concern. White grub damages soybean by feeding on soybean roots, killing young plants, and reducing stands. Insecticide seed treatments have some, but limited effect on grub.

Wireworms. As the name implies, wireworms are wire-like worms that feed on soybean seed, preventing germination.  This leads to poor and spotty stands when populations are high. They may also feed on the underground base of the plant. Later, they may feed on roots. To determine if wireworms are a problem, bait stations can be employed. Seed treatments are effective against wireworm.

This leads to poor and spotty stands when populations are high. They may also feed on the underground base of the plant. Later, they may feed on roots. To determine if wireworms are a problem, bait stations can be employed. Seed treatments are effective against wireworm.

Lesser cornstalk borer can be a problem on seedling soybean; problems on older soybean are infrequ ent. Outbreaks are more likely under hot, dry conditions and in sandy fields with weedy hosts. Larvae of this insect bore into the main stem at or just below the soil surface. Numerous seedlings can be injured by a single larva. Seedlings can be cut off at the soil surface or the tunneling can cause wilting and death. Surviving plants may lodge and be lower yielding. Insecticide seed treatments or other applications are not effective.

ent. Outbreaks are more likely under hot, dry conditions and in sandy fields with weedy hosts. Larvae of this insect bore into the main stem at or just below the soil surface. Numerous seedlings can be injured by a single larva. Seedlings can be cut off at the soil surface or the tunneling can cause wilting and death. Surviving plants may lodge and be lower yielding. Insecticide seed treatments or other applications are not effective.

Insecticide seed treatment to soybean is of limited value in Virginia. Seed treatments can reduce feeding by some species of insects early on the season, for the first 3 to 4 weeks after plant germination. However, we do not typically treat for insects early, nor is there data to support the value or need. Early season insects include thrips (various species) and bean leaf beetle. Ames Herbert, Extension Entomologist, spent several years doing tests across the state trying to determine the value of treating for thrips and was never able to find a yield advantage. Bean leaf beetle can feed on seedling plant leaves, but he has never seen a yield reduction from the feeding. In the north central US, growers use seed treatments to reduce first generation soybean aphid. In Virginia, we do not see aphids until late July or August long after any seed treatment would be out of the plant system. Seed treatments may have some utility for wireworms and grubs.

Kudzu Bug. Although not necessarily an early-season insect, this new pest is showing up early this year just to our south. Little is known about this insect, but we are learning quickly. This insect was discovered in Georgia in 2009, moved into South Carolina in 2010 and through North Carolina in 2011.  It was also found in Patrick County, Virginia in 2011. As of May 2012, it has already been found in at least six N.C. counties and in Greensville County, VA. It feeds on wide range of legume hosts including kudzu, wisteria, some vetches, and soybean. It has several generations per year, moving from sheltered areas such as bark or rocks in the winter to kudzu and then on to soybeans. Like an aphid, it has piercinig and sucking mouthparts, therefore does its damage by sucking juices and nutrients from the plant. Of the studies conducted in 2010 and 2011, it has reduced soybean yield by an average of 21%. We need to track this insect, so timely spray recommendations can be implemented. So if you see this insect, please notify your County Extension office or you can contact Ames Herbert directly at the Tidewater AREC. You will be hearing more about this insect, so stayed tuned.

It was also found in Patrick County, Virginia in 2011. As of May 2012, it has already been found in at least six N.C. counties and in Greensville County, VA. It feeds on wide range of legume hosts including kudzu, wisteria, some vetches, and soybean. It has several generations per year, moving from sheltered areas such as bark or rocks in the winter to kudzu and then on to soybeans. Like an aphid, it has piercinig and sucking mouthparts, therefore does its damage by sucking juices and nutrients from the plant. Of the studies conducted in 2010 and 2011, it has reduced soybean yield by an average of 21%. We need to track this insect, so timely spray recommendations can be implemented. So if you see this insect, please notify your County Extension office or you can contact Ames Herbert directly at the Tidewater AREC. You will be hearing more about this insect, so stayed tuned.

Last year, the Virginia Ag Pest Advisory (an email subscription list) became the Virginia Ag Pest and Crop Advisory blog. As with the old system, you receive weekly emails containing important advisories on your mobile or desktop device, and you can scroll the titles and select only those that are important to you. Normal advisories will be delivered each Friday at 1 am and available for reading first thing on Friday mornings. And as before, there is an ‘Urgent’ option that will be used to provide any advisories that need immediate attention.

Last year, the Virginia Ag Pest Advisory (an email subscription list) became the Virginia Ag Pest and Crop Advisory blog. As with the old system, you receive weekly emails containing important advisories on your mobile or desktop device, and you can scroll the titles and select only those that are important to you. Normal advisories will be delivered each Friday at 1 am and available for reading first thing on Friday mornings. And as before, there is an ‘Urgent’ option that will be used to provide any advisories that need immediate attention.