Deciding whether or not to replant can be a gut-retching decision. I readily admit that the choice to leave the present stand or replant is not a simple one. With the ever-increasing cost of Roundup-Ready soybeans and diesel fuel, the profitability of replanting may not seem a good idea. On the other hand, high prices make replanting more appealing. In the end, your decision should be one based on the estimated dollar gain from replanting. This will require a careful evaluation of the soybean stand and an analysis of yield potential of the present and replanted crop.

In general, there is less benefit of replanting if stands are reduced uniformly across the field. Usually replanting can only be justified where stands have been reduced by half. However, poor stands usually include gaps in addition to merely a lower plant population. These gaps must be accounted for. In addition, one may have a 75-80% stand in parts of the field, while other parts of the field may only have 20-25% of the intended plant population; the decision may be to only replant part of the field.

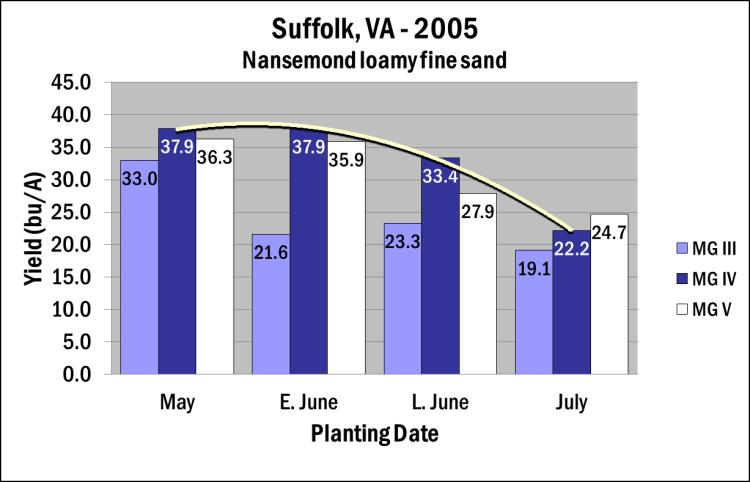

Remember to take into account the yield loss from delayed planting. Up until mid-June, there is very little yield loss from delayed planting. After this, for every day delay in planting yield declines about half a bushel per day. For instance, if replanting in late-June/early-July (about 2 weeks late), your potential yield will have declined by 7 bushels per acre.

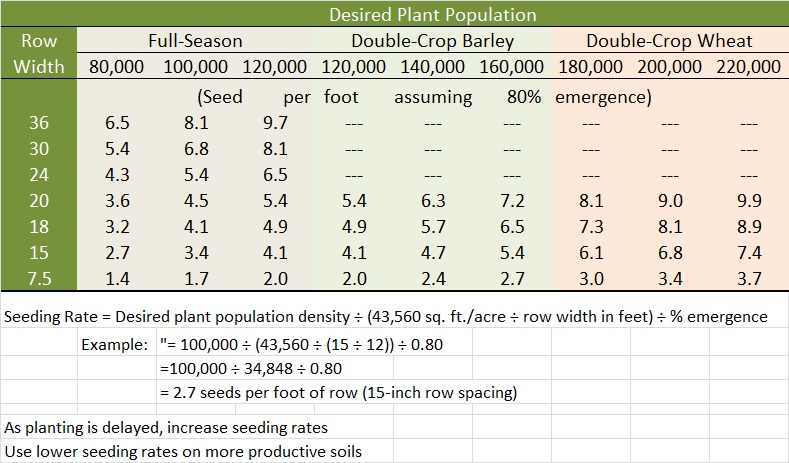

A few more questions must be asked before we can proceed with a step-by-step procedure for estimating the profit of replanting. When considering a replant, do you leave plants in the field and plant through them? In many cases, planting through the poor stand is a possibility. If you’re using rows wide enough to fit a tractor tire comfortably between them, then you can split the rows and plant enough new plants to get the final plant population up to 100 to 120 thousand plants for full-season systems (if re-planting before mid-June) or 180 to 200 thousand plants per acre for double-cropped systems (this may require equipment or tractor tire modifications).

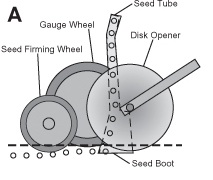

On the other hand, a drill will cut up many healthy plants and make them less productive than the ones that you just replanted. Also, if the drill has wide gauge wheels, then you can severely damage a significant number of plants (there’s a significant amount of down pressure on those wheels – enough to crush a plant on hard soil). And a damaged plant can sometimes act more like a weed than a crop. Recognize that the plants growing in the field are going to be higher yielding that any that emerges after replanting. If you destroy or injure those plants, you’ve just writing off some profit. Therefore, I do not suggest planting through the old stand with a drill.

Another issue is that if you decide to replant, do you switch to an earlier maturity group? There is little need to plant an earlier-maturing variety. Here are two general rules of thumbs:

April/May Plantings: A 3-day delay in planting will result in a 1-day delay in planting. Therefore, if planting 30 days later, the crop will mature 10 days later.

June/July Plantings: A 5-day delay in planting will result in a 1-day delay in maturity. Therefore, if planting 15 days later, the crop will mature only about 3 days later.

Most important is to plant a maturity group that would grow as long as possible (therefore producing an adequate canopy for maximum yield) and still mature before the average frost date. If you’re destroying the old crop and starting over, just make sure that the variety you chose will mature before a frost. Alternatively, if you are planting into the old crop, you may want to choose a variety about one-third to half a maturity group earlier (depending on planting date differences) so that harvest maturity of both plantings will be more in sync. For example, if you planted a relative maturity group 5.6 on June 10, then you could choose a relative maturity of 5.2 to 5.4 if replanting on June 25.

Finally, realize that you’ll need a higher plant population when planting late. Final stand with a double-crop planting should be at least 180 thousand plants per acre. If replanting in July, increase the seeding rate to insure at least 220 thousand plants per acre.

To estimate the profitability of replanting, follow the guidelines listed below. Be sure to incorporate plant population and gaps in your calculations. We’ve found that 2- to 3-foot gaps cause as much or more yield loss that from low plant populations.

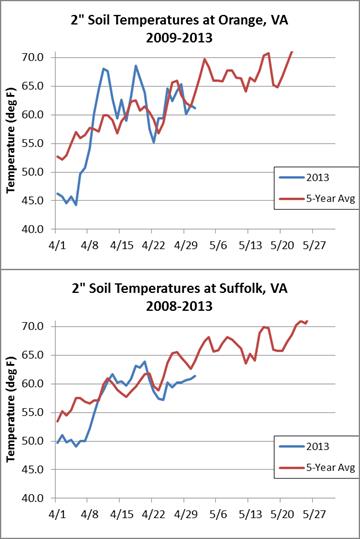

1. Determine the cause of the poor stand. Was the poor stand the result of poor seed quality, cold wet soils, hot dry soils, planting too deep or shallow, soil crusting, herbicide injury, insect or slug feeding, poor soil to seed contact, or disease infection? Determine if the cause can be corrected to avoid a similar situation. If slug or insect feeding or disease is the cause, then you might expect poor stands again.

2. Estimate the stand and percent stand loss due to gaps. Pace off the sections of row 20 paces long in at least 6 areas of the field. Determine (in number of paces) the total length of row lost to 2- to 3-foot gaps. For drilled soybean, this can be interpreted at 2- to 3-foot diameter gaps. Then determine the percent of row lost to gaps. In addition, count and determine average number of plants per foot in sections of row not reduced by gaps. The simplest method is to count the number of healthy plants (capable of recovery) in a length of row equaling 1/1000 of an acre. For instance:

· 36-inch rows = 14.5 feet

· 30-inch rows = 17.5 feet

· 20-inch rows = 26 feet

· 15-inch rows = 35 feet

· 7.5-inch rows = 70 feet

Then, just multiply your counts by 1,000 to get plants per acre.

Or, use the Tables 13.1 or 13.2 to determine remaining plant population. The “hula hoop” method (Table 13.2) is valuable with drilled soybean or when rows cannot be distinguished. This involves placing a circular measuring device such as a hula-hoop on the ground and counting the plants contained within.

|

Table 13.1. Plant populations of different row spacing with different plant counts per foot. |

||||||

|

Plants/ foot |

Row Spacing |

|||||

|

36 |

30 |

24 |

20 |

15 |

7.5 |

|

|

|

Plant Population (1,000’s/acre) |

|||||

|

1 |

15 |

17 |

22 |

26 |

35 |

70 |

|

2 |

29 |

35 |

44 |

52 |

70 |

140 |

|

3 |

44 |

52 |

65 |

78 |

105 |

210 |

|

4 |

58 |

70 |

87 |

105 |

139 |

278 |

|

5 |

73 |

87 |

109 |

131 |

174 |

— |

|

6 |

87 |

105 |

131 |

157 |

209 |

— |

|

7 |

102 |

122 |

152 |

183 |

244 |

— |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 13.2. Hula-hoop method for determining drilled soybean populations. |

|||||

|

No. of Plants |

Inside Diameter of Hula Hoop |

||||

|

30” |

32” |

34” |

36” |

38” |

|

|

|

Plant Population (1,000’s/acre)a |

||||

|

6 |

53 |

47 |

41 |

37 |

33 |

|

10 |

89 |

78 |

69 |

62 |

55 |

|

14 |

124 |

109 |

97 |

86 |

77 |

|

18 |

160 |

140 |

124 |

111 |

100 |

|

22 |

196 |

172 |

152 |

136 |

122 |

|

26 |

231 |

203 |

179 |

160 |

144 |

|

aPlants/acre = no. plants ¸ (3.14 x r2 ¸ 43,560 ft2) where r = radius of hula hoop in feet. |

|||||

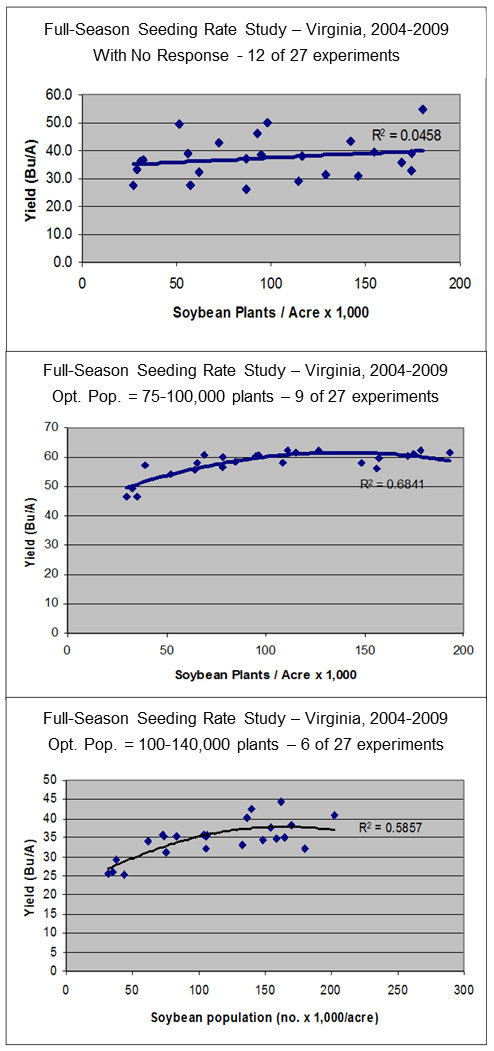

3. Estimate the yield of the poor stand. Use Tables 13.3 and 13.4 to determine percent of yield potential for full-season and double-crop plantings, respectively. Multiply this percentage by the expected yield. This is the yield to expect from the deficient stand.

4. Estimate the yield from replanting. After mid-June, decrease the expected yields an additional half of a bushel per acre per day delay in planting. This is the yield to expect from delayed planting.

5. Determine the gain or loss from replanting. Subtract the expected yield of the poor stand (step 3) from the yield expected from delayed planting. This is the gain or loss in bu/A from replanting. Multiply this number by the expected price ($/bu), using future prices, to obtain gain or loss in $/A.

6. Estimate the cost of replanting. Include per acre cost of tillage, herbicide, fuel, seed, and labor.

7. Determine profitability of replanting. Subtract your cost of replanting from your estimated gain from replanting.

|

Table 13.3. Yield response (% of maximum) of full-season soybeans to deficit standsa. |

|||

|

% Stand lost to gapsb |

Remaining Plant Pop (1,000’s/A) |

||

|

70 |

105 |

140 |

|

|

0 |

95 |

97 |

100 |

|

10 |

93 |

96 |

98 |

|

20 |

91 |

93 |

96 |

|

30 |

88 |

90 |

93 |

|

40 |

83 |

86 |

89 |

|

50 |

78 |

81 |

84 |

|

60 |

73 |

75 |

78 |

|

aSource: Pepper and Wilmot. Managing Deficit Stands. 1991. Illinois Cooperative Extension Cir. 1317. bGaps of 12 inches or more; 30-inch rows |

|||

|

Table 13.4. Yield response (% of maximum) of double-crop soybeans to deficit standsa. |

||||

|

% Stand lost to gapsb |

Remaining Plant Pop (1,000’s/A) |

|||

|

100 |

140 |

180 |

220 |

|

|

0 |

80 |

88 |

95 |

100 |

|

20 |

71 |

79 |

86 |

91 |

|

40 |

61 |

69 |

76 |

81 |

|

60 |

48 |

57 |

64 |

69 |

|

aSource: 2001-2004 experiments, Suffolk, VA. bGaps of 3 feet; 15-inch rows; MG 4 variety |

||||