Rachel Vann, Extension Soybean Specialist – N.C. State University & David Holshouser, Extension Agronomist, Virginia Tech

Now that the weather has turned hot and dry, and with limited rainfall in the forecast over the next ten days, we are starting to get questions about continuing to plant soybeans or halting planting until we catch a rain. There is no consensus on what to do in this situation, but we aim to discuss the pros and cons of the different approaches in this blog post.

Soybean seed must take in 50% of its weight in water to initiate the germination process. Germination is not affected if the seed has imbibed water for 6 hours (seed is swollen, but seed coat in not broken), then it dehydrates to 10% moisture. If the seed has imbibed water for 12-24 hours (seed coat is broken but no radical has emerged) then dehydrates to 10%, germination may be reduced 35-40%. If the radical has emerged and the seed dehydrates to 10% moisture, few if any seedlings will survive (Holshouser, 2012). What we want to avoid with any approach discussed below is exposing the seed to enough moisture to start germination but not enough for the seed to get out of the ground.

The general optimum planting date range for planting soybeans across North Carolina was identified by Dr. Dunphy as May 1 to June 10. This optimum planting range varies from year-to-year based on rainfall, soil water holding capacity and soybean maturity, but the goal is to get the soybean plants to lap the middles before reproductive growth begins. We still have 10 more days before we get to the end of that optimum range this year and parts of the state have a chance for rain before June 10. Continuing to wait to plant is more of a concern for our growers who still have seed from early maturing varieties to plant (<MG5), as these varieties will have less time for vegetative growth prior to the beginning of reproductive development. The three major options growers in the region are facing are discussed below.

- Plant shallowly in the dry and hope for enough rain to get the seed out of the ground. If you decide to take this approach, you want to ensure you achieve uniform seed depth and that you are not allowing the seed access to moisture below the seed that could lead to variable emergence. This approach would be less risky in clean-tilled situation where you are more confident that you have dried the soil out at shallow depths. Dr. Dunphy said he has seen soybeans planted shallowly into dry conditions before that have sat in the ground >5 weeks and still had excellent emergence when rainfall occurred. The biggest risk with this approach is that you catch a small rain that allows the soybean seed to imbibe water but does not provide enough moisture to get the soybeans out of the ground. We would also suggest you exercise caution using this approach in a no-till situation where you would be more likely to see problems with lacking uniformity of moisture across the field leading to variable seed access to moisture and ultimately emergence variability. In many cases, part of the field will have adequate moisture to get the soybeans out of the ground, other parts will be completely dry as in tilled conditions, and much of the field will be in between. Those in-between areas are likely to have enough moisture to swell the seed and/or initiate germination but not have enough moisture to allow the seedling to emerge. We have had several inquires on the impact of planting into dry conditions on soybean seed treatments. What we can say is that fungicidal seed treatments are less likely needed in this situation where we already have high soil temperatures and lacking soil moisture than they are in earlier planting situations where the soils are cool and wet.

- Plant deep to the moisture. Under most conditions, soybeans should be planted 0.75 to 1.5 inches deep. Soil temperatures are high enough right now to germinate and emerge quickly, even at deeper depths than recommended. But soybeans should not be planted deeper than 2 inches. We’ve talked to several growers and County Agents across the region who are not finding soil moisture until 3 to 4 inches deep; we definitely do not recommend planting this deep. Growers should exercise caution using this approach if your soils are prone to crusting, because a heavy rainfall could seal the soil before the soybeans emerge. In addition, if the planter pushes the soil down a little in tilled conditions, creating a ridge of fluffy soil on each side, a heavy rain will cause this fluffy soil to move into that furrow and possibly add another ½ to 1 inches of soil to your depth. If you are going to go this route, check the emergence score on the variety.

- Keep the seed in the bag until the next time we catch rain. This is the safest approach

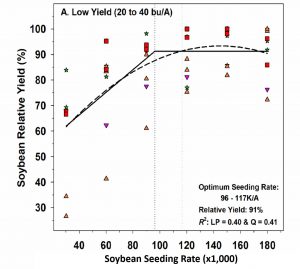

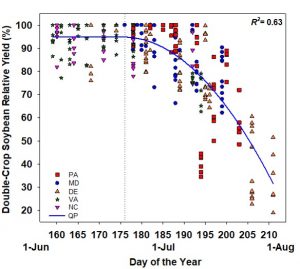

at this point. Based on historical data, we have another 10 days or so before we start seeing yield declines from delayed planting. Parts of the state have a chance of rain in the next 10 days. Data from recent research throughout the Mid-Atlantic shows that each day delay in planting past mid-June can result in a ½ bu/A or more yield loss and in general these yield declines begin in the second or third week of June; we still have some time before we get to that point.

at this point. Based on historical data, we have another 10 days or so before we start seeing yield declines from delayed planting. Parts of the state have a chance of rain in the next 10 days. Data from recent research throughout the Mid-Atlantic shows that each day delay in planting past mid-June can result in a ½ bu/A or more yield loss and in general these yield declines begin in the second or third week of June; we still have some time before we get to that point.

Whatever decision a grower makes, uniform seed placement in critical to achieve uniform emergence and ensure each seed has as equal of access to water as possible. We have discussed the importance of uniform emergence in soybeans here: https://soybeans.ces.ncsu.edu/2019/04/how-important-is-uniform-emergence-in-soybeans/

In conclusion, there are advantages and disadvantages to each planting option discussed, but we still have time to plant soybeans in our region before we see drastic yield declines. All options discussed will likely result in delayed emergence due to environmental conditions.