Virginia cotton requires a thrips control product at planting to preserve yield and avoid maturity delays. This is especially true since the arrival of tarnished plant bugs. Any maturity delay early-season will likely magnify plant bug injury. Cotton planted at the end of April and first week of May has put on 1-2 true leaves. It is time to scout for thrips injury and make foliar applications when necessary.

Levels of injury to cotton seedlings rated from ‘0’ (no damage) to ‘5’ (dead terminal

or plant) from thrips. Injury at ‘2-3’ or above approximates a threshold for intervention with an

insecticide application. (Photo and caption from Kerns et al., 2018)

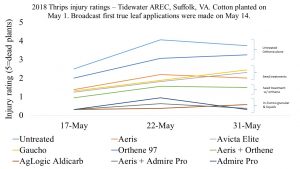

Using a seed treatment alone will likely require a foliar spray based on research from the Tidewater AREC. In-furrow aldicarb and in-furrow imidacloprid with a seed treatment should not need a foliar spray. Scout cotton planted with in-furrow imidacloprid alone and determine if a foliar application is necessary (often it is not – saving you time and money).

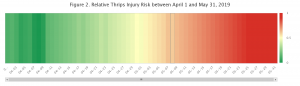

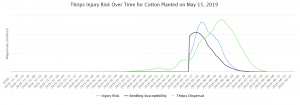

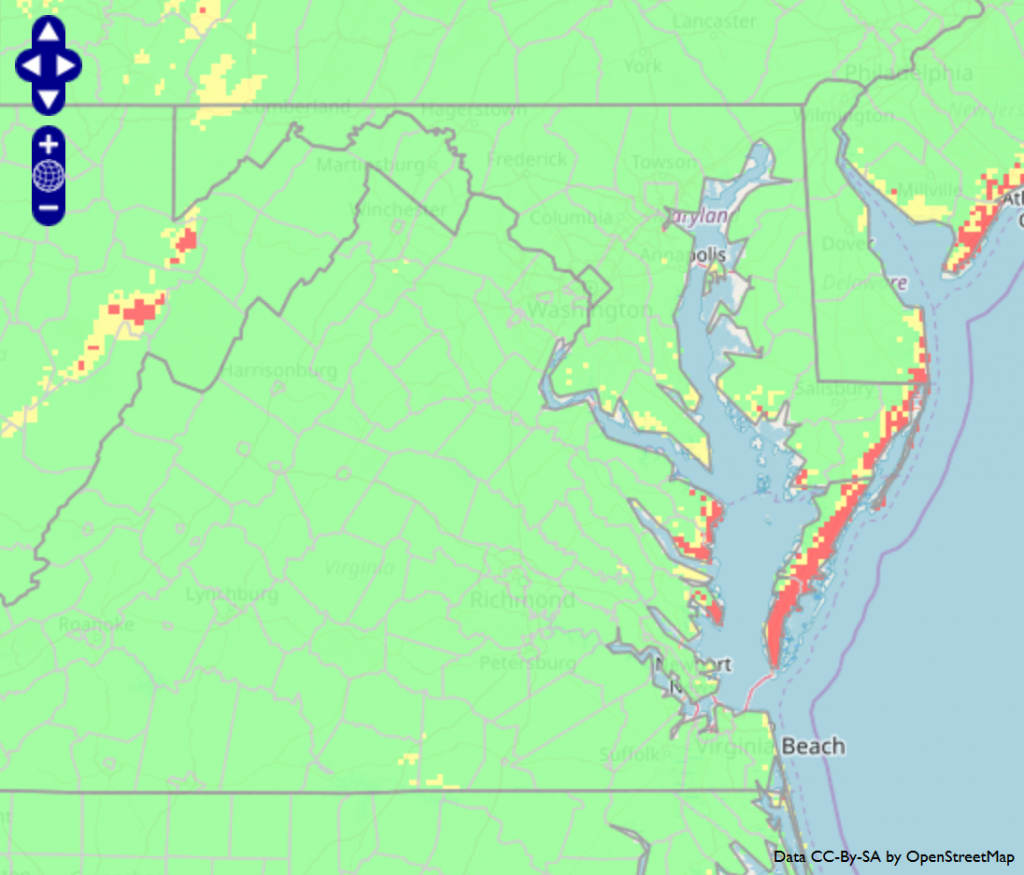

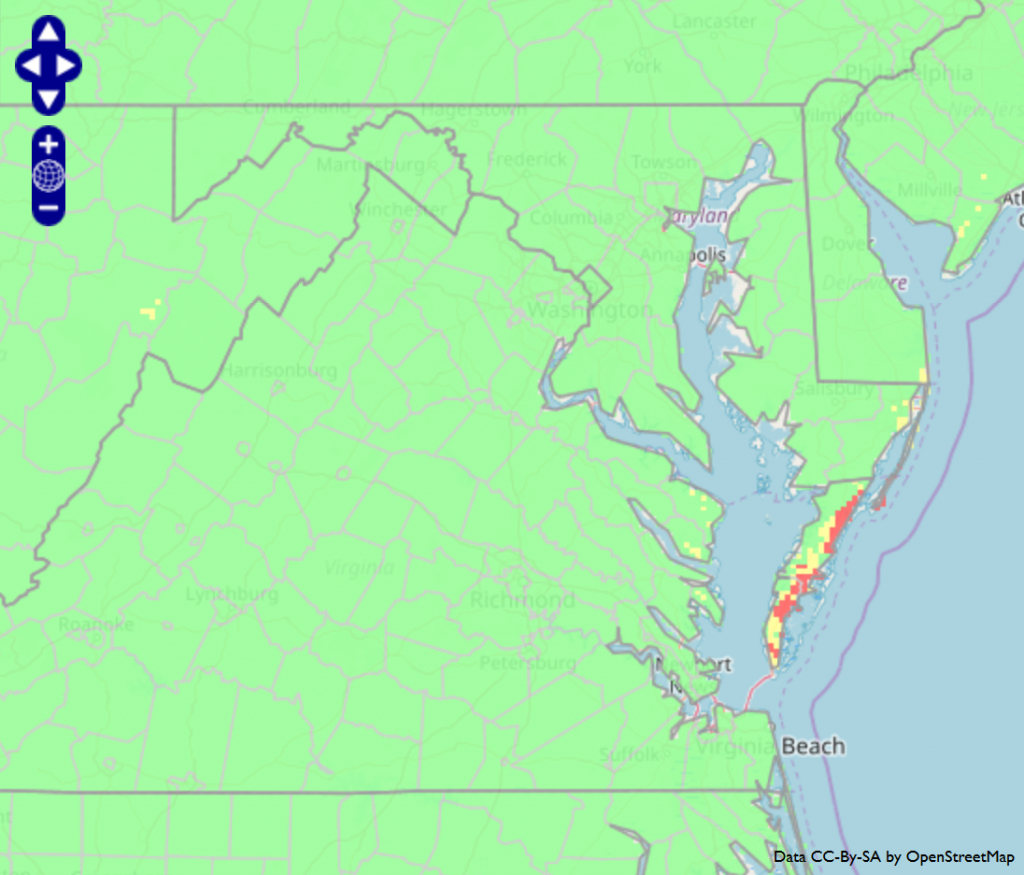

All cotton planted in Virginia is under high risk for thrips injury. NCSU prediction model shows risk increasing in later-planted cotton. This model was highly accurate in 2018.

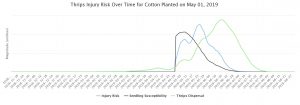

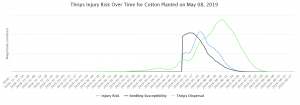

Tips for foliar applications: Consider plant-date and growing conditions. Cotton planted late-May into warm soil may not need a foliar spray. Do not apply foliar acephate if plants are growing fast with no to minimal thrips injury. Thrips injury is likely for all cotton planted in Virginia and risk will be high until plants are no longer susceptible. The three diagrams below from the NCSU model show when seedling susceptibility declines based on planting date (May 1, May 8, May 15). The blue line on these diagrams shows you when risk for thrips injury is highest.

Spraying is most effective when the first leaf is the size of a pencil tip to a mouse ear. I recommend a 6-8 oz. rate of acephate. Several scenarios may be responsible for reduced efficacy of sprays:

1. Rain. Acephate is not a rain fast product. Consider reapplying if necessary.

2. Resistance. Acephate at 3 oz. per acre has become less effective in spray tests. Rotate to Radiant if another spray is required or use a higher rate.

3. Species composition. Tobacco thrips are most common in VA, but western flower thrips can co-infest. Acephate is less effective on this species. Rotate to Radiant if another spray is required.

As always, call/text/email me with any questions. Good luck and happy planting!