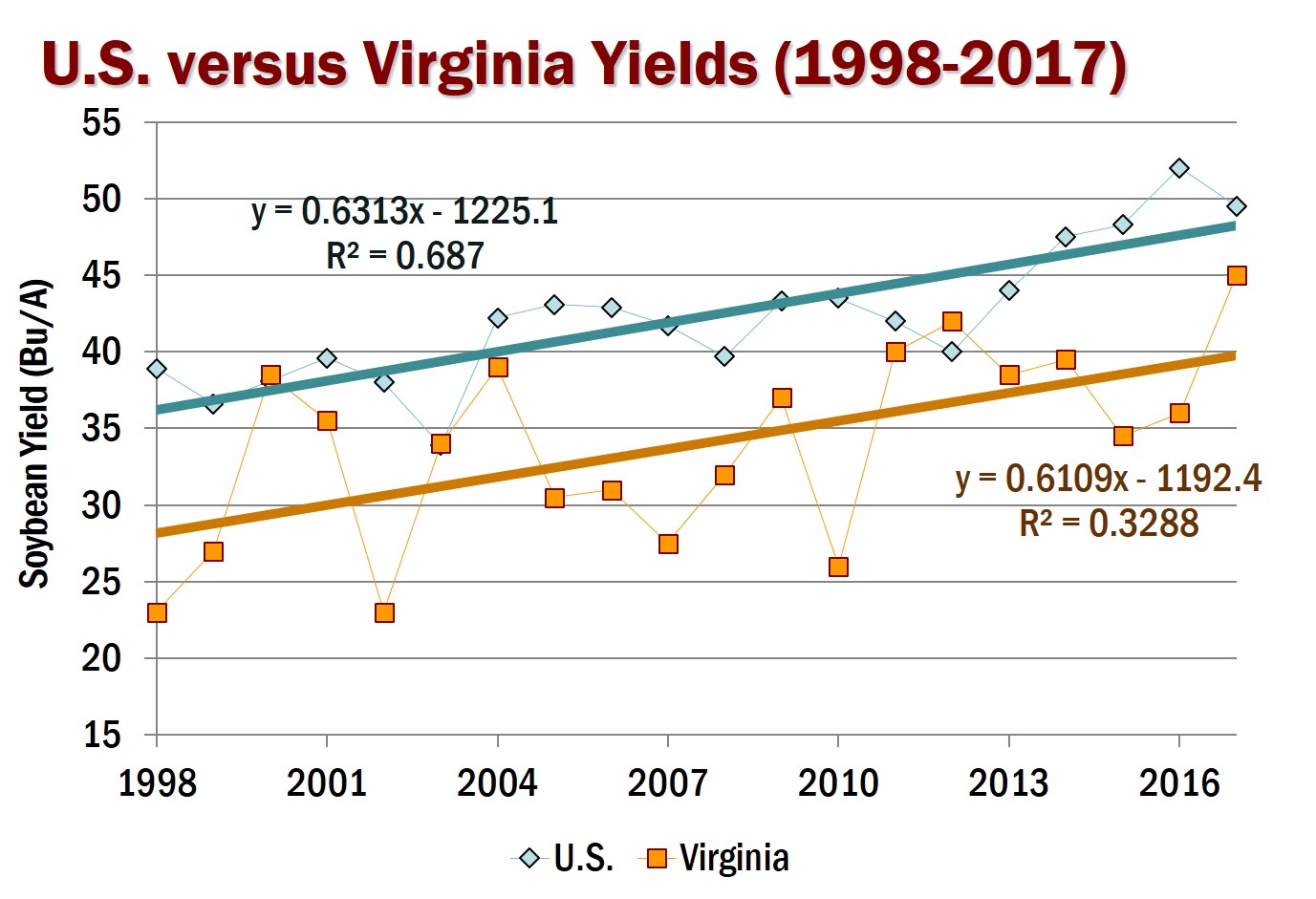

Variety selection continues to be one of the most important decisions that we can make. It is also one of the first steps to take that insure success. It’s a hard choice because there are so many varieties available. Still, this choice is one that will affect your profitability throughout the year.

Soybean yields in our variety tests have increased by an average of 0.4 bushels per year over the last 30 years. Some of this increase is due to better varieties, some is due to better management. In those tests, the highest and lowest yielding varieties varied by 20% or more (8-10 bushels). It is therefore clear that making the wrong choice will seriously impact next year’s soybean crop. Unfortunately, environment (rainfall, temperature, soil type, field, etc.) affects yield variation more than variety – there is always lots of year-to-year and site-to-site variation. Still, each variety has specific strengths and weaknesses that make it more or less suited for any given situation.

Putting the Right Variety in the Right Field

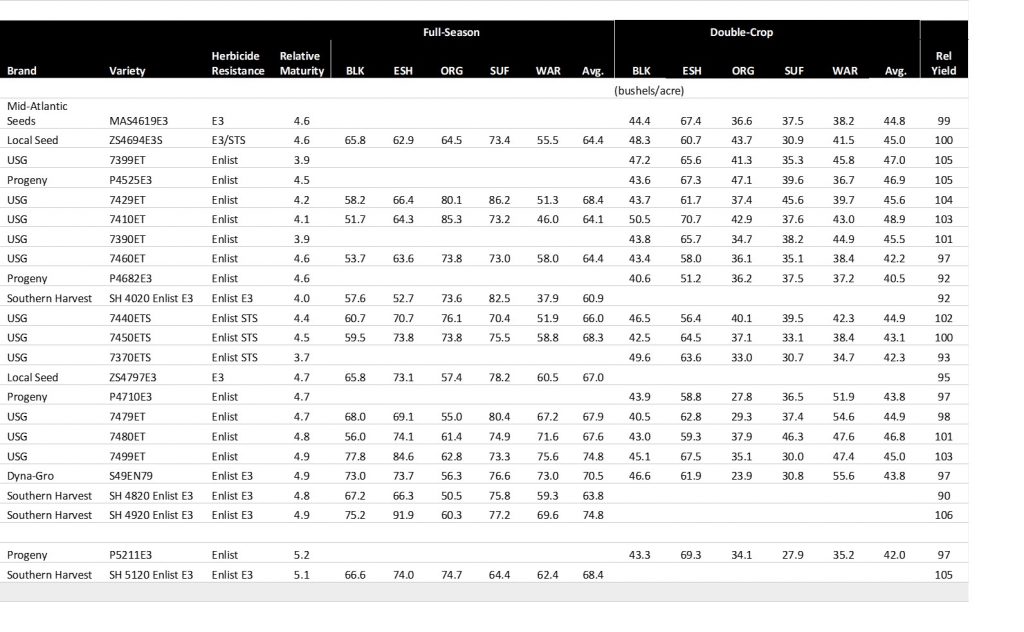

With all this variation, it is very important that you place the right variety in the right field. This will be influenced by 1) planting full-season or double-crop; 2) maturity; 3)herbicide tolerance; 4) disease and/or nematode tolerance; and finally 5) yield potential. There are also a number of other factors that differentiate varieties such as shattering and lodging susceptibility, height, branching ability (thin vs. bushy), seed size, seeds/pod, protein and oil content, other specific traits, etc.), but these will rarely affect your bottom line. Although all of the top five things I listed are important, yield potential is clearly what is of most interest. However, if you do not pay attention to numbers 1 through 4 first, your yield potential can be low.

To cover all of the things that make variety selection important would take more words than this blog will allow, so we will first focus on the choosing the right maturity.

Relative Maturity Choice: Spreading Out Environmental Risk

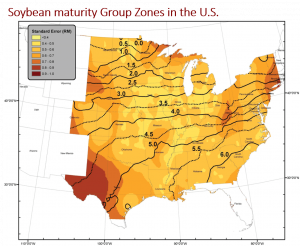

First, I should say something about early planting of an early-maturing variety. I define this as planting in April or early May a variety that is about one full maturity group earlier than the maturity that is most adapted, based on historical data, for your area.  First, early-planted early-maturing varieties will always have a greater risk of poor quality seed. The seed of these varieties are maturing during September and early October, when the weather is relatively warmer. Warm and wet weather are perfect conditions for seed decay. 2018 has been one of the worse years for this, primarily due to excessive rainfall and much warmer September temperatures. To the right is an example of a maturity group (MG) 3 soybean planted in April in Madison County (MG 4 is the most adapted maturity for this area). Clearly, you don’t want to end up with this. While early maturing varieties have their advantages, their associated risks should keep the percentage of acres planted to a minimum.

First, early-planted early-maturing varieties will always have a greater risk of poor quality seed. The seed of these varieties are maturing during September and early October, when the weather is relatively warmer. Warm and wet weather are perfect conditions for seed decay. 2018 has been one of the worse years for this, primarily due to excessive rainfall and much warmer September temperatures. To the right is an example of a maturity group (MG) 3 soybean planted in April in Madison County (MG 4 is the most adapted maturity for this area). Clearly, you don’t want to end up with this. While early maturing varieties have their advantages, their associated risks should keep the percentage of acres planted to a minimum.

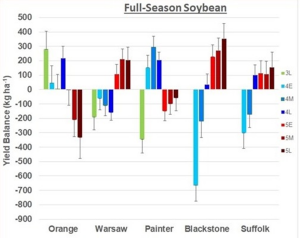

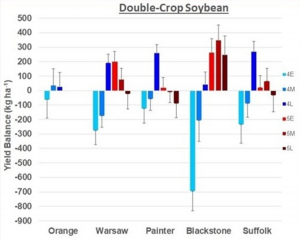

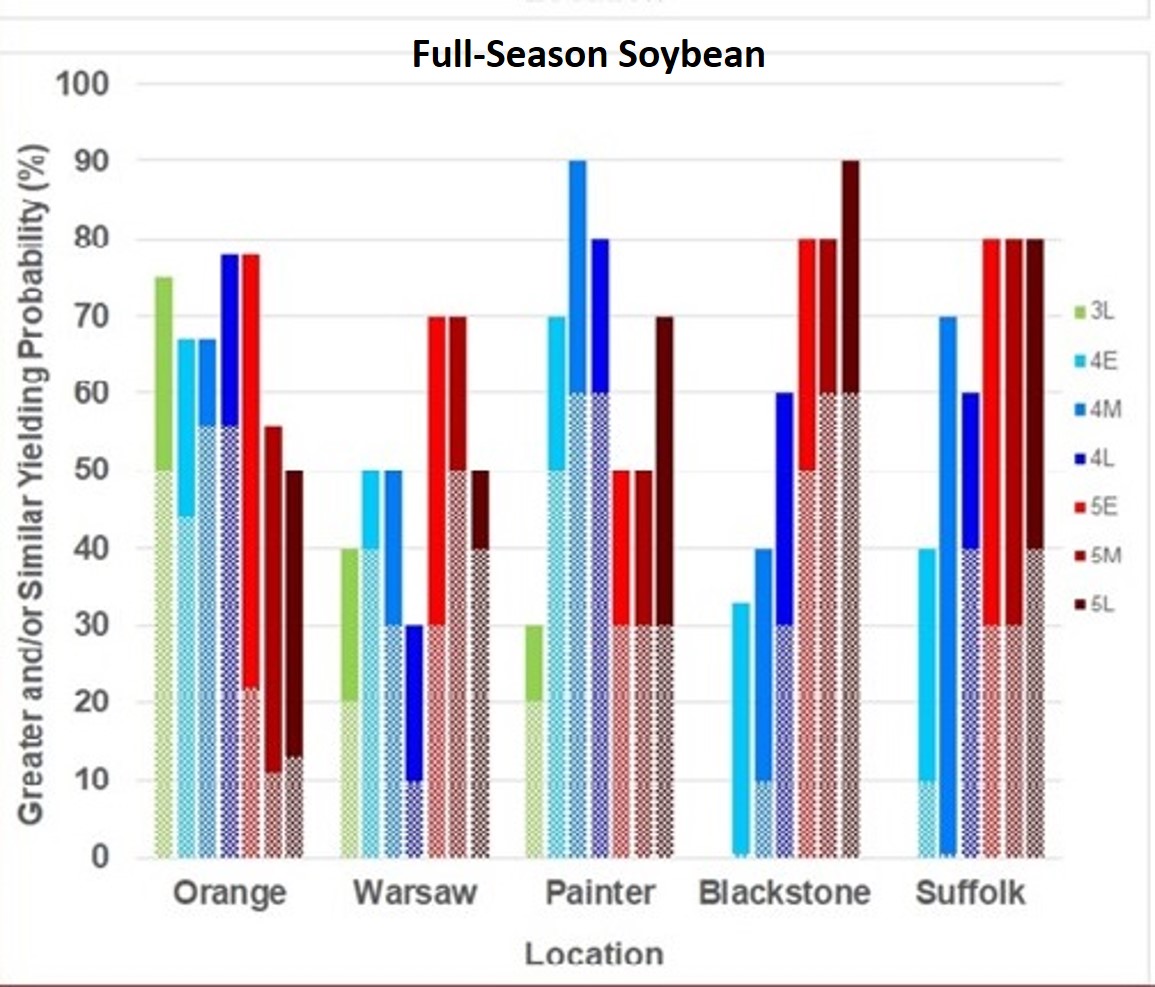

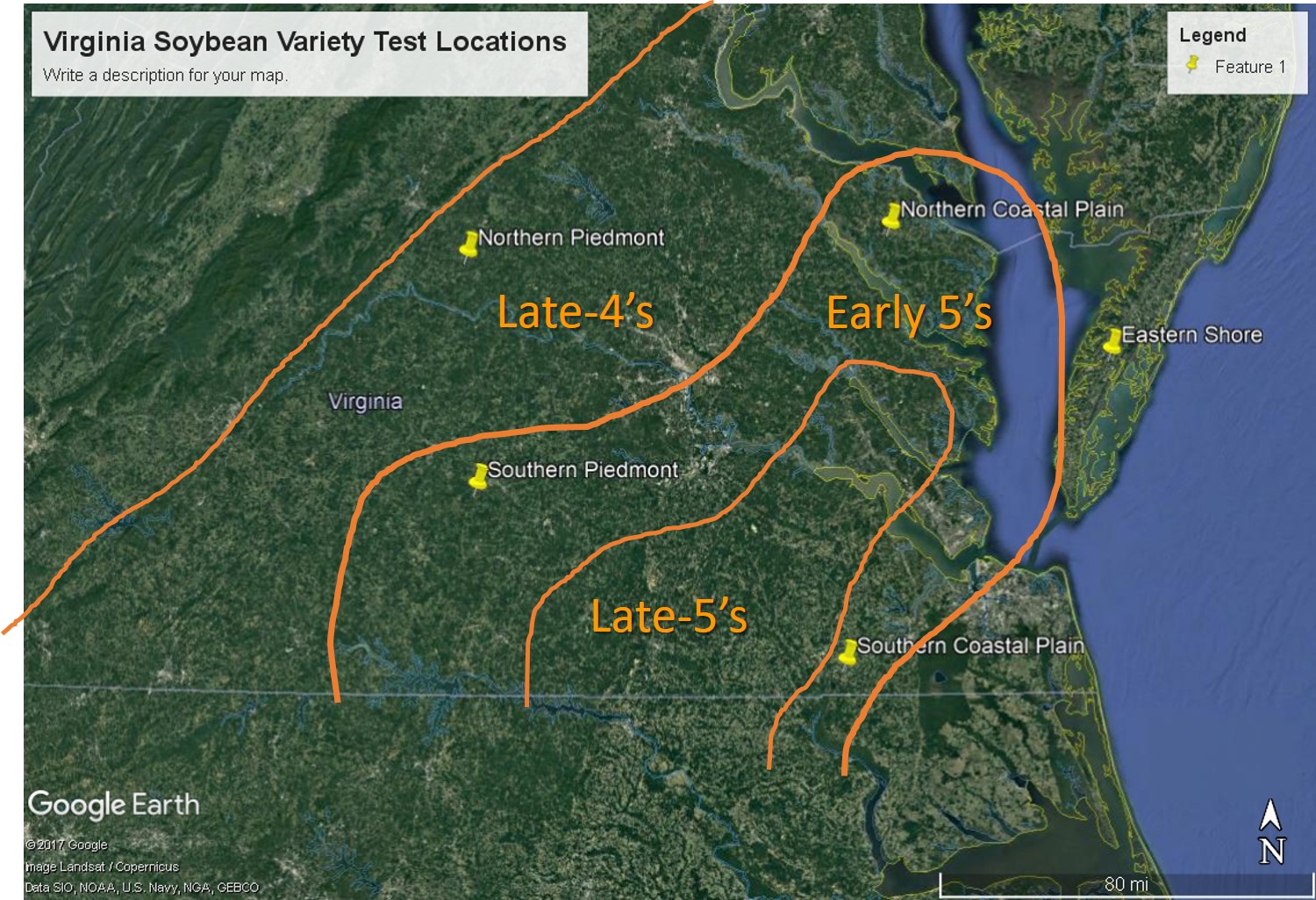

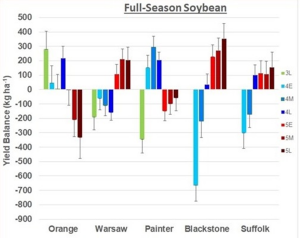

On the other hand, do not keeping all varieties in a tight maturity range. The performance of varieties within a certain maturity range will almost always depend the environment that they experience during pod and seed fill. If conditions are good (adequate rainfall, moderate temperatures, good soils) during that time, yields will be high. Unfortunately, the weather cannot be predicted in our humid southeastern U.S. environment. While late-July and early-August are generally our hottest and driest times of the year, we have just as good of a chance of going through a hot and dry period in June as well as July as well as August, and sometimes in September. Still, on average, certain relative maturity ranges yield more than others in the south central part of Virginia. Below are the average yield balance (no. of bushels/acre greater or less than average) of a range of soybean maturities tested in our full-season variety tests over the last 10 years, separated by location.

I’ll use our Southern Piedmont location (Blackstone) as an example of a location that shows the greatest yield gap between the earliest and latest varieties (nearly 15 bushels!). This is likely due that area typically experiencing the more stress (hot and dry) from late July through August than other regions.

Similar but on the opposite end of the spectrum, MG 3 and 4 varieties work best at the Northern Piedmont (Orange) location. Maturity group 5 varieties generally not as adapted in that northerly environment.

The northern and southern Coastal Plain sites (Warsaw and Suffolk) behave similarly to Blackstone – MG 5 outperform MG 4 varieties; but the yield gap between relative maturities is not as wide.

Our Eastern Shore location does not follow the same trend of MG 5’s being the highest average yielding varieties as one moves south and east.

Note that maturity group (MG) 5 varieties relatively better in the more eastern and southern locations of Virginia’s mainland, while MG 4 varieties tend to do better in our most northwestern location (Orange) and on the Eastern Shore (Painter). While MG 3’s don’t yield as well, the group 4’s are the highest yielding. Why? I attribute it to two things: yield potential and temperature. In general, this site has over time been one of our highest yielding sites. Although rainfall patterns are similar to other locations in Virginia, it is our coolest location (and there is usually a breeze) – both likely a water effect. Therefore, the site experiences less stress. So, pushing the critical pod- and seed-filling stages slightly earlier in the year are not as problematic.

So, should you stick only with maturities that perform best on average? Not necessarily. Using Blackstone as an example, note that although the late-group 4 varieties yield less than MG 5’s on average, they yield much better than earlier 4’s. And late-4’s yield just as well as 5’s in Orange and Suffolk. I stress that these are averages – 10-year averages of all varieties within those relative maturity ranges. Is it possible for the MG 4 varieties to yield more than the 5’s in Blackstone or Warsaw? Is it possible for MG 5’s to yield more in Painter? Yes! It just does not happen as often.

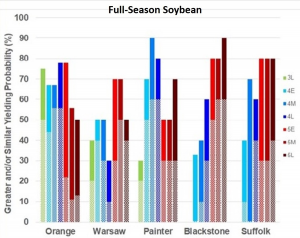

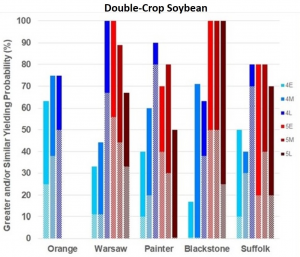

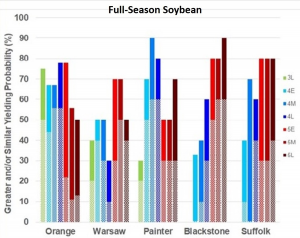

We took that same data and calculated the probabilities, not absolute yields, of obtaining similar or greater yields of all relative maturity groupings tested. The results are below.

Once again, to use the Blackstone data as an example, we can see that growing a late-MG 5 variety will yield at least as much as all of the other relative maturities 90% of the time (bar height). In addition, there is a 50 to 60% chance (height of the hatched portion of the bar) that the 5’s will yield significantly more than the 4’s. So, it seems that you will never go wrong with those varieties, correct? You’ll probably (~80% chance) not go wrong by growing a large percentage of those varieties, but should you should you only plant MG 5’s? I suggest that you do not grow only MG 5 varieties. There is still a 10 to 20% chance that the 5’s will yield less than the other maturities. Plus, there is a 60% chance that late MG 4 varieties will yield just as much as MG 5 varieties (and a 30% chance that they will yield more).

Once again, to use the Blackstone data as an example, we can see that growing a late-MG 5 variety will yield at least as much as all of the other relative maturities 90% of the time (bar height). In addition, there is a 50 to 60% chance (height of the hatched portion of the bar) that the 5’s will yield significantly more than the 4’s. So, it seems that you will never go wrong with those varieties, correct? You’ll probably (~80% chance) not go wrong by growing a large percentage of those varieties, but should you should you only plant MG 5’s? I suggest that you do not grow only MG 5 varieties. There is still a 10 to 20% chance that the 5’s will yield less than the other maturities. Plus, there is a 60% chance that late MG 4 varieties will yield just as much as MG 5 varieties (and a 30% chance that they will yield more).

Painter is another good example. Although there is a yield gap between the 4’s and 5’s, there is a 50 to 70% chance that MG 5 will yield as well as MG 4 varieties. And there is a 30% chance that they will yield more! You can use the same thought process for the other locations.

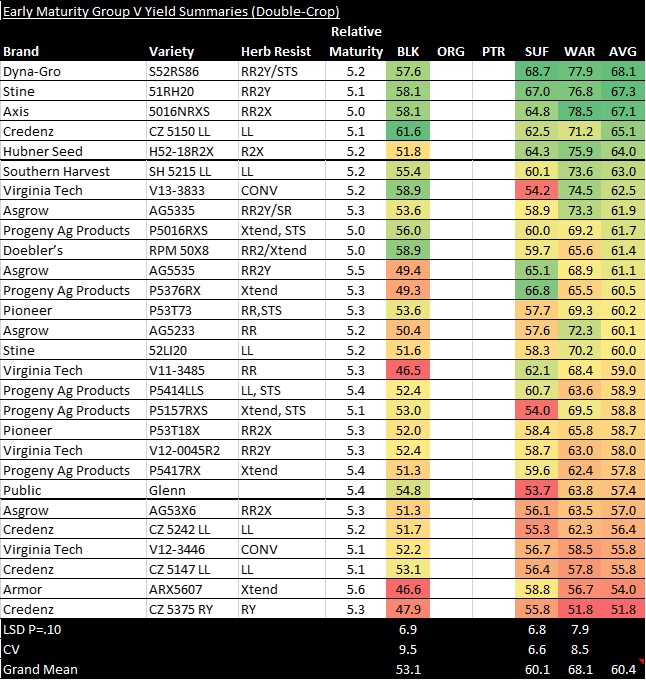

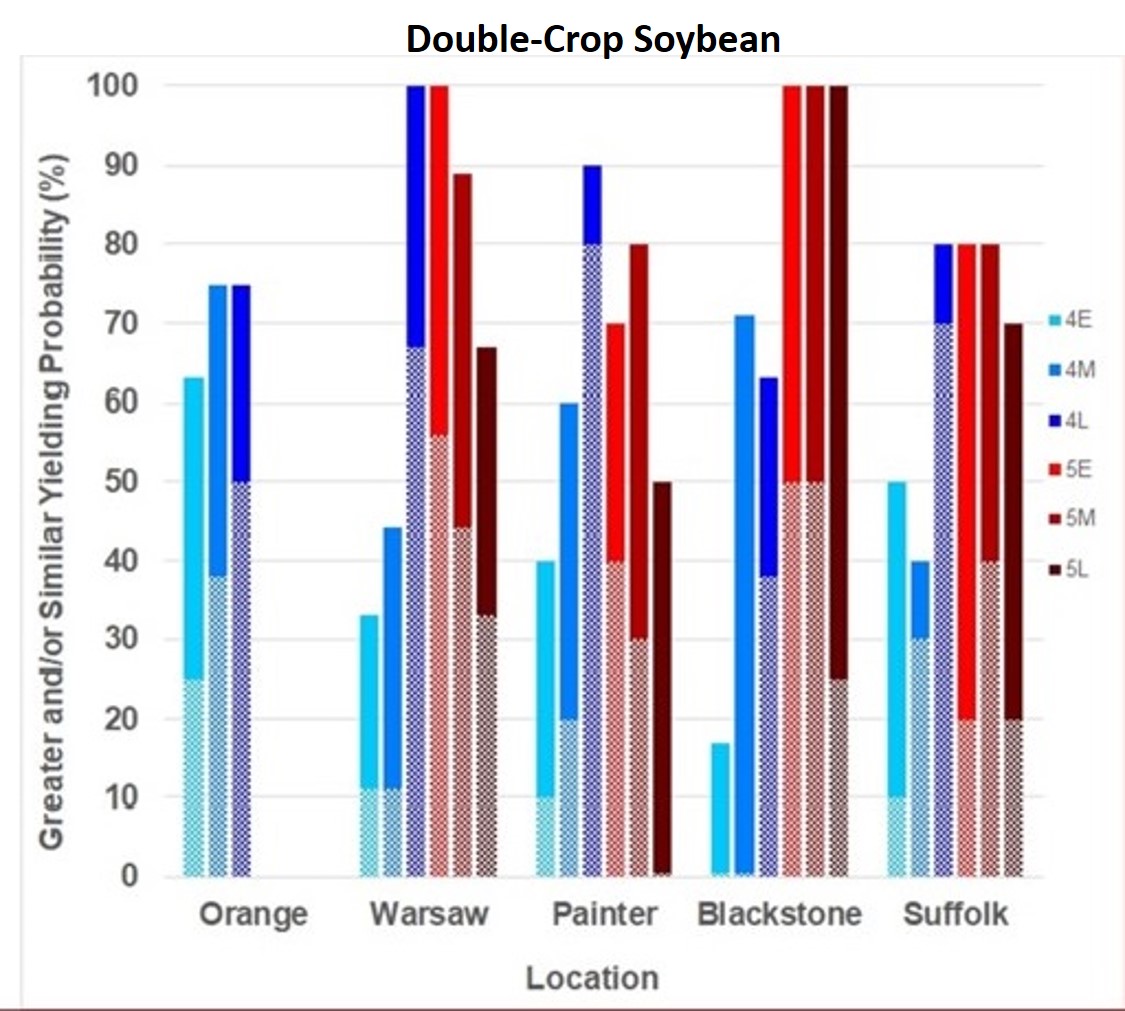

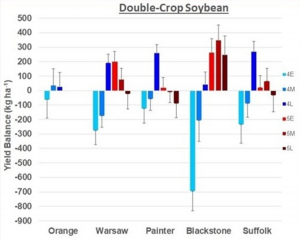

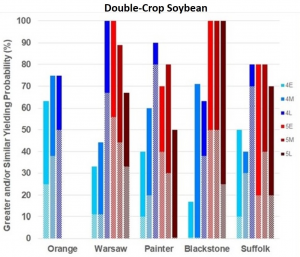

Below are the same graphs for double-crop tests.

The Right Mix of Maturity Groups in Virginia. So, what is the right mix of maturity groups? I suggest the following:

The Right Mix of Maturity Groups in Virginia. So, what is the right mix of maturity groups? I suggest the following:

Southern Piedmont

- Plant 60 to 80% of your land to MG 5 varieties. We have also found that later maturities generally do better on our more droughty soils, so take that into consideration if possible.

- Plant 20 to 30 % to late-MG 4 varieties (4.7-4.9). If possible, plant these on your higher-yielding soils. We have found that this range of maturities have our greatest yield potential throughout Virginia if the weather cooperates.

- Plant 0 to 20 % to mid-MG 4 varieties. These are risky, especially on droughty soils or in double-crop settings. It is highly likely that these varieties will experience some (or a lot) of stress during the seed and pod fill stages. Plus, seed quality will almost always be poorer than other maturities. If you do grow these, harvest as soon as possible as seed quality will continue to degrade with time. Don’t plant these in April or early May. This places the most critical times of development (pod and seed fill) during late-July and August. And seed quality will be even worse since they will likely mature during the warmer part of the year. Still, yield potential can occasionally be quite high.

Southern Coastal Plain (same comments apply regarding droughty soils and seed quality)

- Plant 30 to 60% of your land to MG 5 varieties.

- Plant 30 to 50 % to late-MG 4 varieties (4.7-4.9).

- Plant 10 to 20 % to early- and mid-MG 4 varieties.

Northern Coastal Plain (same comments apply regarding droughty soils and seed quality)

- Plant 30 to 60% of your land to MG 5 varieties. In double-crop systems, reduce that percentage to 30 to 50%.

- Plant 30 to 50 % to MG 4 varieties (4.7-4.9). In double-crop systems, increase that to 50 to 70% late-4’s and plant 10-20% early-or mid-4’s.

- Plant 0 to 20 % to late-MG 3 varieties.

Eastern Shore (same comments apply regarding droughty soils and seed quality)

- Plant 20 to 40% of your land to MG 5 varieties.

- Plant 50 to 70 % to late-MG 4 varieties (4.7-4.9).

- Plant 10 to 20 % to early- and mid-MG 4 varieties. Plant 0-10% in double-crop.

- Plant 10 to 20% to late-MG 3 varieties.

Northern Piedmont (same comments apply regarding droughty soils and seed quality)

- Plant 0 to 20% of your land to MG 5 varieties. Don’t plant MG 5’s double-crop.

- Plant 60 to 80 % to MG 4 varieties (4.7-4.9).

- Plant 10 to 20 % to mid- or late-MG 3 varieties.

The proportion of MG 4 and 5 will ultimately depend on your risk tolerance. Note that as you move west and north, the risk of an early frost is greater; therefore, growing lots of late-maturing varieties may not be a great idea, especially double-crop, and the probability of slightly earlier maturities doing better is greater.

Hopefully, this will give you some guidance in choosing your maturities within the next few weeks.

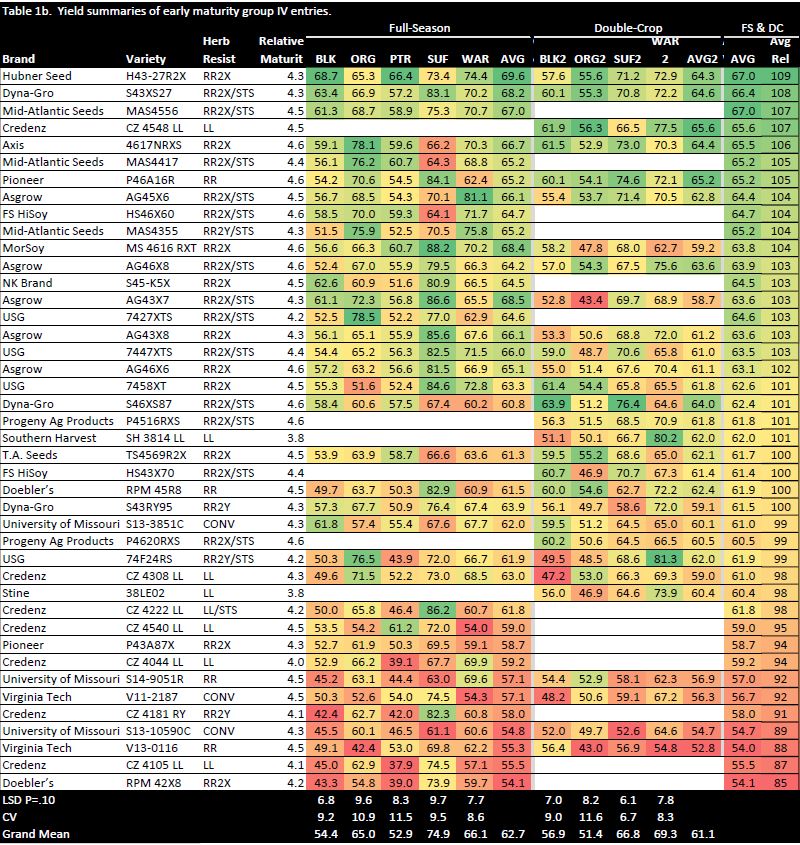

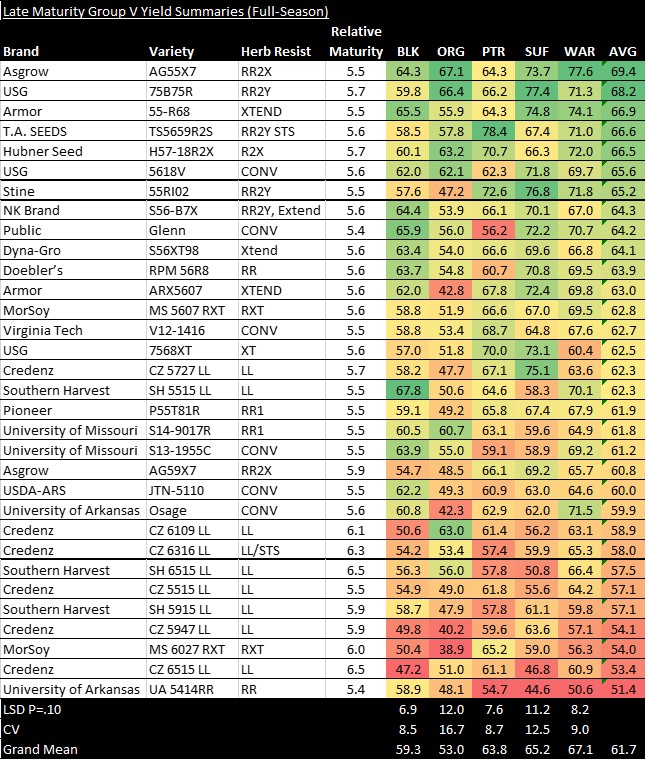

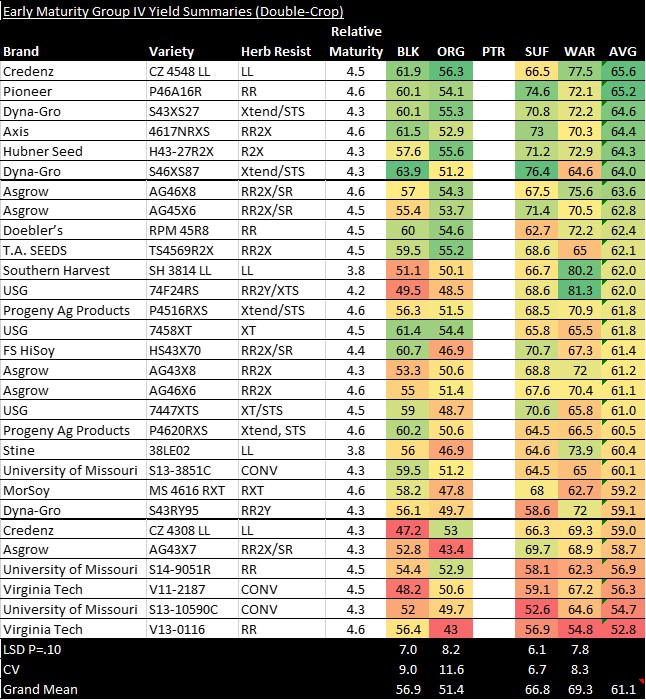

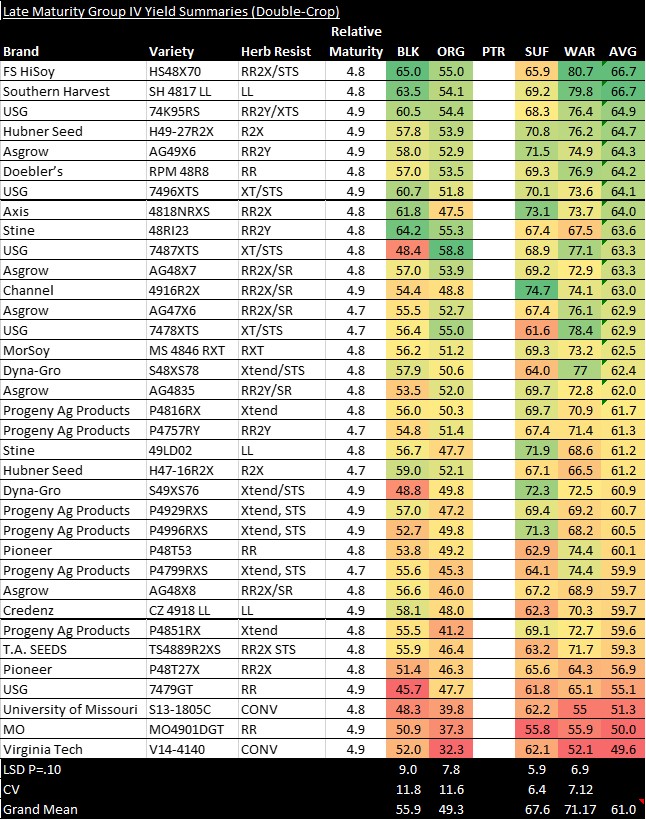

IMPORTANT: Keep in mind that the yields and yield balances shown are an average of all varieties in those relative maturity groupings. This does not mean that every variety in those grouping perform in this manner on every field. Make sure that you first the variety that meets your match your field’s pest management needs; then, select a high-yielding variety within that relative maturity range.