Initial results from the 2016 Virginia state wheat and barley tests are available in excel format at:

The full document and summary is coming soon.

Initial results from the 2016 Virginia state wheat and barley tests are available in excel format at:

The full document and summary is coming soon.

Late blight was found in Accomack County, VA yesterday on potato. Growers on the Eastern Shore and other areas of the Commonwealth should scout their fields and take preventative measures. Please let us know if you have any questions. For more information on this potentially devastating disease of potato and tomato visit: https://pubs.ext.vt.edu/ANR/ANR-6/ANR-6_pdf.pdf

It’s hard to believe, but June is here and we need to start thinking about increasing our soybean seeding rates. I’ve been recommending only 100 to 115 thousand seeds per acre for full-season production, enough to give you 70 to 80 thousand plants – yes, that’s all you need to maximize yield.

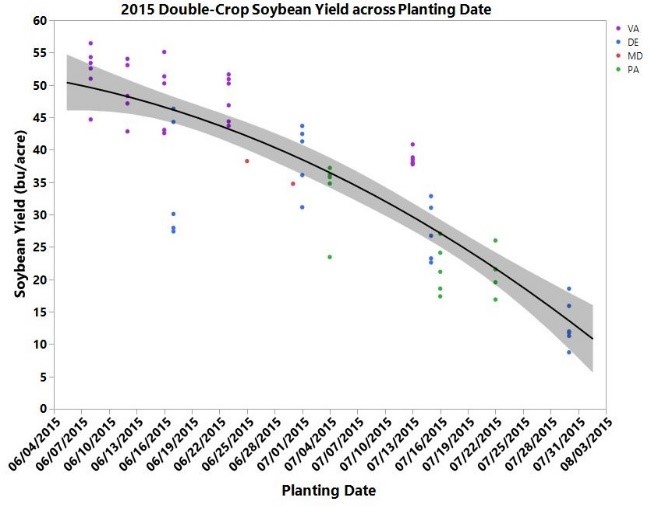

But as the season gets shorter, yields will start falling with delays in planting date. On average, we lose about 1/2 bushel/acre per every day we delay planting after the middle of June. The graph below shows the results of last year’s 4-state early wheat harvest/soybean planting double-crop study. Note that yield does not decline very much during the first week or two of June, but rapidly drops off afterwards.

The main reason for this yield decline is that the crop struggles to develop enough leaf area to capture 90-95% of the sunlight by early pod development, due to the shorter growing season. We can alleviate some of this by narrowing rows and increasing seeding rate.

The main reason for this yield decline is that the crop struggles to develop enough leaf area to capture 90-95% of the sunlight by early pod development, due to the shorter growing season. We can alleviate some of this by narrowing rows and increasing seeding rate.

I usually suggest that farmers plant enough seed to result in a final plant population of 180,000 plants/acre for double-crop soybean. That means planting 200,000 to 220,000 seed/acre. Yes that is a lot of seed, but my research shows that yields (and profit) continue to increase up to this seeding rate, especially when planting is delayed until late-June and early-July.

There are stipulations. More productive soils and irrigated soybean usually require less seed. Good years that allow lots of quick growth require less seed (but who can predict a good year?). Later maturity groups may require slightly less seed. Less seed are needed as you move south (growing season is longer and you can plant a later relative maturity). I think that a soil profile that is full of water at soybean planting (this year) might allow less seed to be planted – but I have not documented that – It just makes sense to me that plants will grow better when the small grain has not depleted most of the subsoil moisture.

What about now? How many seed/acre do we need to plant in the first week of June? Here are my suggestions. Keep in mind that these are general guidelines; you need a gradual increase in seed/acre. I’m assuming 80 to 85% emergence for June/July plantings. To easily determine how many seed you need per row foot, see VCE pub 3006-1447, Suggested Soybean Seeding Rates for Virginia

May: 100 to 115K

June 1-7: 120-140K

June 8-14: 140-180K

June 15-21: 180-200K

June 22-30: 200-220K

July: 220-250K

We are seeing yellow and stunted corn around Virginia du e to many different factors that range from nutrient deficiencies to cool and wet growing conditions. Take a look at this article to give you a few reasons for this poor looking corn and different things to consider prior to making your sidedress nitrogen applications. Yellow_Corn_26May2016

e to many different factors that range from nutrient deficiencies to cool and wet growing conditions. Take a look at this article to give you a few reasons for this poor looking corn and different things to consider prior to making your sidedress nitrogen applications. Yellow_Corn_26May2016

Our overall mild winter and wet spring are the kinds of conditions that favor survivorship and early development of stink bug populations. Because of these conditions, this could be a summer when we see higher than normal stink bug infestations in a lot of crops including field corn, cotton and soybean. Brown stink bugs are already being found in small grain fields and areas of North Carolina are reporting pretty heavy stink bug pressure on seedling field corn. See this article by Dr. Dominic Reisig at the NCSU station on Plymouth for details https://entomology.ces.ncsu.edu/2016/05/how-to-avoid-a-stink-bug-disaster-in-corn-2/

We need to be thinking ‘stink bugs’ this summer and aligning our field scouting, sampling and threshold efforts in that direction as the summer progresses—and that applies to cotton and soybean fields as they mature.

It’s been many years since we’ve seen a true armyworm (see the attached image) infestation in our small grain crop, but one is reported to be ongoing in the barley and wheat fields on the Eastern Shore. These caterpillars can do two types of damage—leaf feeding and head cutting. Leaf feeding is rarely extensive enough to warrant control, especially if fields are within a couple of weeks of harvest. Head cutting is less tolerable. For some reason no one has been able to explain, caterpillars will sometimes eat through the stem below the heads casing them to drop to the ground. Finding otherwise healthy looking heads-short stems on the ground is a good indicator that true armyworms are present and still active. It is often hard to find them on plants during the day as they typically feed more at night and seek cover under plant residue during the day. When we have worked with this pest, we found that fields with the most plant residue on the soil surface tended to have the heaviest infestations.

We do have thresholds for true armyworm for those motivated to scout for them. As a general rule, barley should be treated if the number of armyworms exceeds one per linear foot between rows and most of the worms are greater than 0.75-inch long. In wheat, armyworms tend to nibble on the tips of kernels rather than clip heads; thus, populations of two to three worms per linear foot between rows are required to justify control. In high management wheat fields with 4-inch rows, treatment is recommended when armyworm levels exceed 3 to 5 per square foot of surface area, or per linear foot of row.

If a treatment is warranted, there are a few good choices but the PHI (Pre Harvest Interval) may be a challenge. Some work we did many years ago showed that pyrethroids were generally effective but have a PHI of 14 days (example, Mustang Max) to 30 days (example, Baythroid), which could be a problem for barley, wheat not so much. Lannate has a PHI of 7 days but did only an OK job in our trial and not as good as the pyrethroids. We chalked that up to the fact that although Lannate has great efficacy against most caterpillar species, it has almost zero residual activity. So a day-time spray may not have had as much horsepower by the evening when caterpillars become active. Since our work was done, several new products have been introduced to the market that we have not tested, like Prevathon (PHI 14 days), and Besiege (PHI 30 days). These should work well. See the Pest Management Guide Field Crops 2016, 4-49, p. 53 for more product listings (http://www.pubs.ext.vt.edu/456/456-016/Section04-Insects-1.pdf).

With any treatment, coverage will be essential so deliver the highest volume you can live with and direct it to go as deep into the canopy as possible.

EPA just granted a Section 18 for use of Transform™ WG in Virginia against sugarcane aphid in sorghum. Transform (50% a.i. sulfoxaflor), manufactured by Dow AgroSciences, may be applied through April 8, 2017 on a maximum of 16,591 acres of sorghum fields (grain and forage) in the following counties: Accomack, Albemarle, Alleghany, Amelia, Appomattox, Augusta, Bedford , Botetourt, Brunswick , Campbell, Caroline, Carroll, Charlotte, Charles City, Culpeper, Cumberland, Dinwiddie , Essex, Fauquier, Floyd, Fluvanna , Franklin, Frederick, Gloucester, Goochland, Greensville, Halifax, Hanover , Henrico, Isle of Wright, George , King William, King and queen , Loudon, Louisa, Luneburg, Madison , Mathews, Mecklenburg, New Kent, George , Prince William, Rockbridge , Rockingham , Russell, Southampton, Spotsylvania, Suffolk, Surry, Sussex, Virginia Beach, Washington, Westmoreland, and Wythe.

The following directions, restrictions, and precautions must be observed. Foliar applications may be made by ground or air at a rate of 0.75-1.5 oz of product (0.023-0.047 lb a.i.) per acre. A maximum of 2 applications may be made per year, at least 14 days apart, resulting in a seasonal maximum application rate of 3.0 oz of product (0.09 lb a.i.) per acre per year. Do not apply product 3 days pre-bloom or until after seed set.

To minimize spray drift and potential exposure of bees when foraging on plants adjacent to treated fields: applications are prohibited above wind speeds of 10 miles per hour (mph) and must be made with medium to course spray nozzles (i.e., with median droplet size of 341 µm or greater). A restricted entry interval (REI) of 24 hours applies to all applications. Do not apply within 14 days of grain or straw harvest or within 7 days of grazing, or forage, fodder, or hay harvest.

Environmental Hazards Statement: “This product is highly toxic to bees exposed through contact during spraying and while spray droplets are still wet. This product may be toxic to bees exposed to treated foliage for up to 3 hours following application. Toxicity is reduced when spray droplets are dry. Risks to pollinators from contact with pesticide spray or residues can be minimized when applications are made before 7:00 am or after 7:00 pm local time or when the temperature is below 55 degrees Fahrenheit (°F) at the site of application.”

We will provide updates on the presence and spread of sugarcane aphid as the season progresses.

Gowan has a new supplemental label for Sandea on cucumber, allowing for a 14 day pre-harvest interval. This label will be on the bottle next production run, but for the time being growers wanting to use the supplemental label will need to have a copy of the supplemental label on file. This new label will replace the 24c (Special Local Needs label) label that covers the same use. If you have any questions do not hesitate to contact me. Below is the supplemental label.

Sandea 81880-18 cucumbers (aprvd 5-11-16)

We were hoping to be about half way finished with our soybean plantings by now, but we haven’t put a planter in the field in two weeks. The rain continues to delay us, but I hope that we will get back into the field next week.

The rain and cooler weather has lowered soil temperatures somewhat and this means that we need to take a few extra precautions, especially pertaining to seedling disease. I wrote a detailed blog a few years ago on seedling disease; little has changed and, for more details, you can view that blog here:

Fungal Seedling Disease in Soybean

Planting soybean in cool soil will lead to delayed emergence and increased chance of seedling disease that can reduce stands, weaken emerged plants, and inhibit early-season growth. I stress that the greater time required for emergence, the greater probability that the seed will become infected with soil-borne disease. If you are planting into cool soils, I strongly suggest using fungicide-treated seed as an insurance against seedling disease. These treatments will protect the seed and seedling if emergence is delayed.

But, seed treatments should not be a substitute for other practices that encourage rapid seedling emergence. Here is my checklist for insuring a good stand free of seedling disease:

I was recently made aware of a long list of fungicides involving the European Union and their restriction on some chemical residues on peanuts. Over the last couple of weeks there were rumors that these restrictions have been relaxed but apparently these rumors are unfounded, I was told. Well, for the industry that exports peanut this is quite serious because any trace of any of the chemical on that list may result in failure to their business. The list includes many fungicides for bacterial diseases, which are not a common problem in the VC region; others, however, like Tilt Bravo SE are. For the sake of staying informed and alerted at what it is and what may come, here I provide that list, with the recommendation that growers do not use any product on that list. Notice to Growers – Products Not To Be Used