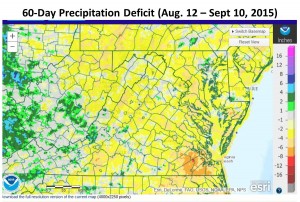

As I’ve driving throughout Virginia these past few weeks, one thing that is evident is the large amount of vegetative growth on our full-season soybean. While adequate vegetative growth is necessary for maximum yield, it can work against the crop in seasons that experience August/September droughts. In much of Virginia, soil moisture was depleted rapidly due to this large amount of growth and the lack of rain in August and September resulted in pod and seed abortion. I’ve seen many fields that look relatively good from the windshield, especially after some rains perked up the plants. But, closer examination revealed few pods or few seed in the pods. In general, I think that farmers will be disappointed in their full-season yields.

on our full-season soybean. While adequate vegetative growth is necessary for maximum yield, it can work against the crop in seasons that experience August/September droughts. In much of Virginia, soil moisture was depleted rapidly due to this large amount of growth and the lack of rain in August and September resulted in pod and seed abortion. I’ve seen many fields that look relatively good from the windshield, especially after some rains perked up the plants. But, closer examination revealed few pods or few seed in the pods. In general, I think that farmers will be disappointed in their full-season yields.

On the other hand, timely rains during August and/or September in so me parts of Virginia allowed these full-season soybean to match this seemingly excessive growth with lots of pods and seed. In such scenarios, 60 to 80 bushels per acre are possible. The only thing that may work against such a crop is, ironically, excessive vegetative growth that is causing or might lead to lodging. I always remind those that complain about lodging that 20 bushel soybean do not usually lodge.

me parts of Virginia allowed these full-season soybean to match this seemingly excessive growth with lots of pods and seed. In such scenarios, 60 to 80 bushels per acre are possible. The only thing that may work against such a crop is, ironically, excessive vegetative growth that is causing or might lead to lodging. I always remind those that complain about lodging that 20 bushel soybean do not usually lodge.

Now we have Hurricane Joaquin bearing down on us. This could greatly change our yield potential, especially in our large full-season soybean with a good pod and seed set that is not yet fully mature. With this in mind, I thought that I would review lodging’s effects on soybean yield.

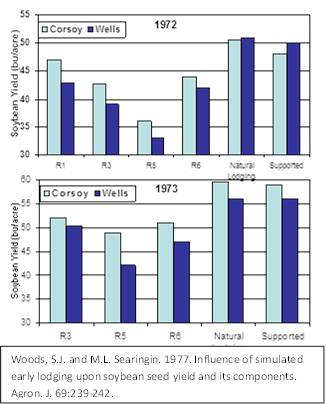

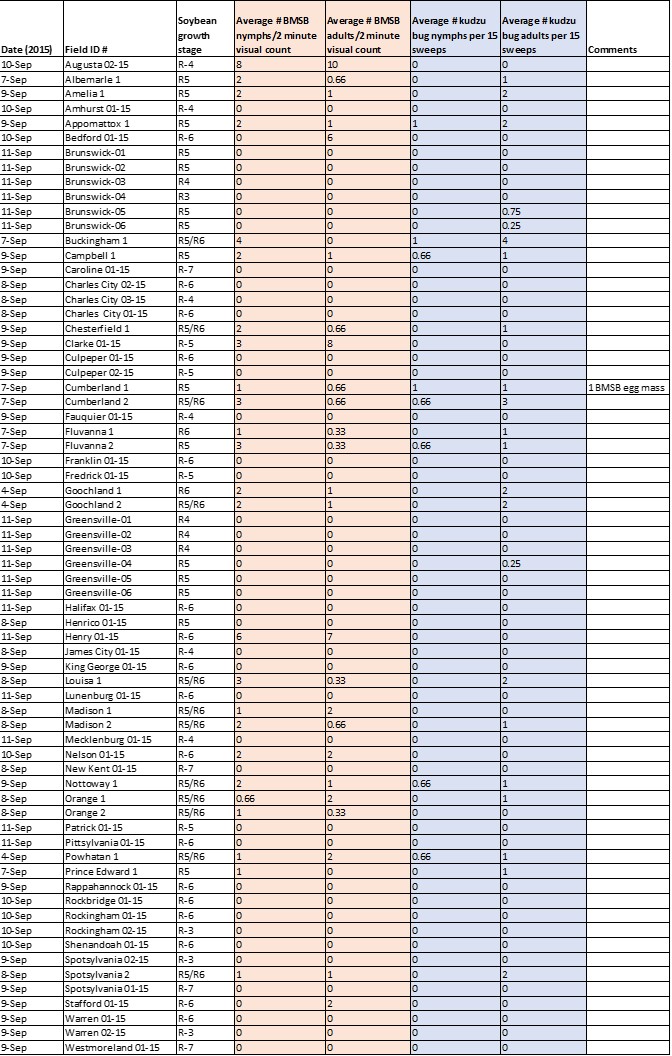

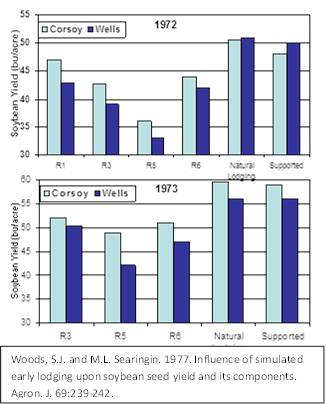

How much will the lodging cost us in yield? This will depend on the degree of lodging and the stage that the soybeans were in. In general, I’d say that our full-season crop is rapidly approaching maturity. Fields planted to earlier maturity groups are physiologically mature (R7, 98-100% of the final yield has accumulated), some are ready for harvest. Many fields are still in the R6 (full seed) stage. Most double-crop soybeans are in the R5 (beginning seed, seed are not yet touching in the pod) and R6. Yield is most severely affected by lodging when the lodging occurs at the R5 stage. Although yield is still affected at R6, yield losses are only half as severe at this stage. Although at a more susceptible stage, double-crop soybeans are much shorter and will not likely have as severe lodging as more full-canopied full-season soybean.

So, what’s my estimate on the amount of yield loss? First, we have to distinguish harvest or traffic loss from physiological yield loss. Harvest losses can vary anywhere from 3-10% depending on many factors. In some cases, we may have to run the combine of the most severely lodged soybeans in one direction.

There is little data on physiological yield loss, but what’s out there seems to be pretty consistent. What do I mean by physiological yield loss? That’s the loss in yield from lodging if all of the soybeans that are now on the plant can be harvested. In controlled studies where researchers simulated lodging and compared it to a crop that was artificially supported, losses have ranged from 0% to over 30%. Why such a range in yield loss? It depends on the severity of lodging and the stage of development in which the lodging occurred.

Let’s first address the severity of lodging. Soybean researchers have traditionally rated lodging on a scale of 1 to 5 as follows:

1.0 = almost all plants erect

2.0 = either all plants leaning slightly, or a few plants down

3.0 = either all plants leaning moderately (45O angle), or 25-50% down

4.0 = either all plants leaning considerably, or 50-80% down

5.0 = all plants down

Yield loss will be minimal unless most plants are leaning at a 45O angle or more. Otherwise, yield losses can range from 10-35%, depending on the stage in which the lodging occurred.

Why does lodging cause yield loss? It’s not completely clear, but the generally accepted reason is a reduction in net photosynthesis. With less photosynthesis, there is less energy going to the developing pods and seeds. When plants are lodged, relatively less of the upper leaves and more of the lower leaves are exposed to sunlight. The upper leaves are more photosynthetically active and the lower leaves are less active. When lodging occurs, the entire energy-producing mechanism is disturbed. In other words, we are now exposing less of the most productive leaves and more of the least productive leaves to the sun. So, yield will decline.

Let’s assume that lodging rated above 3.0 will cause a 10-30% loss. Now the severity of the yield loss will depend on the development stage that the soybean plant was in. As I said earlier, there’s little hard data on this subject, but a few older experiments give us some information. In a study conducted in 1972-73, S.J. Woods and M.L. Swearingin of Purdue University indicated that the R5 stage was the most critical time for lodging to occur. At this stage, yield was reduced by 18-32%. At stages R3 and R6, yield was reduced by  12-18% and 13-15%, respectively. Details of that experiment are shown to the right.

12-18% and 13-15%, respectively. Details of that experiment are shown to the right.

In that study, the plots were manually lodged with a long aluminum bar at the indicated soybean stage. Although lodging ratings were not given, I would consider it to be in the 3.5 to 4.0 range from the description given. Two varieties were tested. ‘Corsoy’ was more susceptible to lodging, but was able to branch more; therefore, it yielded higher when lodged. ‘Wells’ is more resistant to lodging, but did not branch as much; therefore, was unable to compensate as much for the lodging. In the natural lodged plots, only slight (2.0 or less) lodging occurred.

From the above data and a few other studies, I’d estimate that where lodging is moderate to severe and the soybean are in the early R6 stage, we could lower our yield potential by 10-15%. If the plants are still in the R5 stage and lodging is severe, losses could be 15-25%. If soybeans are in even later stages (mid-R6), yield loss will be less. If physiologically mature (R7, one pod on the plant has reached is final mature color), 98 to 100% of the dry matter has accumulated and losses will be nearly zero (assuming no harvest losses). Most of our full-season soybeans are close to physiological maturity (R7). Plus, plants with fewer leaves lodge less.

In summary, there may be some yield loss due to Hurricane Joaquin. Yield losses will be greater with later maturity groups or in double-crop acres that have good growth. But, hopefully, the hurricane will move off the coast and the only soybean we need to worry about lodging are those with very high yield potential.