Before I get into tips for soybean, I must emphasize one must focus on the entire double-crop wheat-soybean system. Both crops must contribute to profit; one crop cannot carry the other. You will may save some input costs such as lime, fertilizer, and rent (making those seasonal cost spread over two crops) with the double-crop system, but certain costs such as soybean seeding rate will increase. In the end, these inputs roughly equal out with the exception of land rent that can vary greatly over Virginia.

With that said, the most important thing to insure a profitable double-crop system is yield, yield of both crops. Without a minimum of 80+ bushel/acre wheat and 33-35+ bushel soybean, the system will not likely be as profitable as the full-season soybean system, especially with today’s low prices.

Assuming that you will intensely manage both crops during the growing season (note that intensely managing does necessarily not equate to greater input costs, but instead greater attention), the most important thing that anyone can do right now for greater yields is to harvest the wheat crop as soon as possible, and then immediately plant the soybean. Our 3-year, 5-state (PA, MD, DE, VA, NC) project conducted just a few years ago clearly confirmed that this is one of, if not the most important decision that a double-crop farmer can make. In that project, we generally showed a rapid decrease in both wheat and soybean yield with delayed harvest and planting after mid-June. Wheat yield declined anywhere from 0.5% to 2.5% per day, depending on location and year, versus wheat that was harvested at 18-20% moisture. This was largely due to rapidly declining test weights afterwards. And we also noted that quality decreased in many test locations. Note that if wheat is harvested this wet, then it will need to be dried almost immediately. I don’t recommend this unless you have a continuous-flow drier or have a buyer willing to take the high-moisture wheat without severe price dockage.

Although we found a benefit to the wheat crop, probably the bigger benefit however to harvesting wheat at high moisture is earlier planting of the soybean. On average the soybean yield began to decrease about ½ bushel/acre per day by mid-June, but this increased to 1-2 bushels per day once we got into late-June (more northerly Mid-Atlantic states) and early-July (more southerly Mid-Atlantic states). This resulted in a major income difference.

Just to re-emphasize this most important point, harvesting the wheat and planting the soybean ASAP is the most important thing a farmer can do to make this system as or more profitable than a full-season soybean system. The current weather is not helping with this (we could have harvested much of our wheat this week), but hopefully next week will bring drier weather.

Here are some other tips that are very important when planting double-crop soybean.

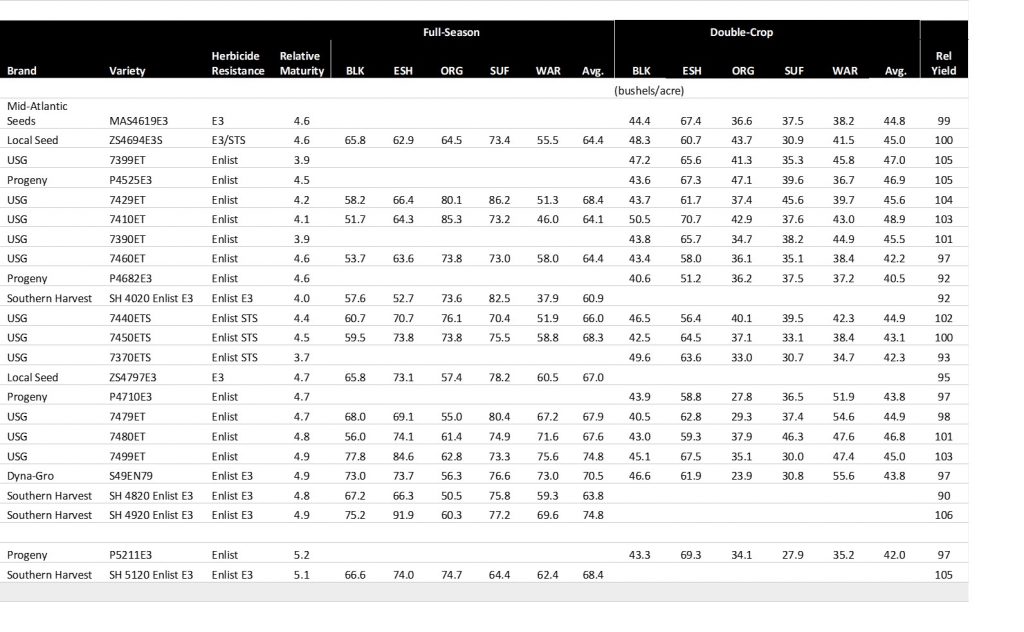

Variety Selection. Select the latest maturing varieties that will mature before the frost. This will assist with growing as much leaf area and having as many reproductive nodes as possible. Plant the earlier maturing varieties in this maturity range on your best soils and the later relative maturities on the poorer-yielding land.

Always Plant in Narrow Rows. I prefer 15 to 20 inch rows seeded with a planter that singulates the seed. Seed singulation insures uniform seed placement within the row and no big gaps between plants. The other option is to plant with a drill, which achieves the narrow rows but results in what many refer to today as a “controlled spill”. This results in many gaps, 2 or 3 seed planted in the same place, and generally lower yields (we proved this in some on-farm double-crop studies in the early 2000s). Still, a drill is better than 30-inch (or wider) rows at such a late planting date.

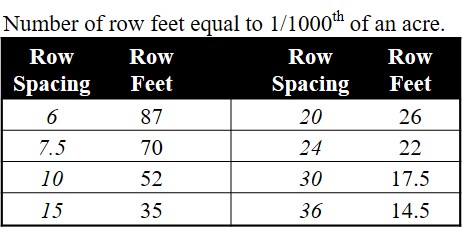

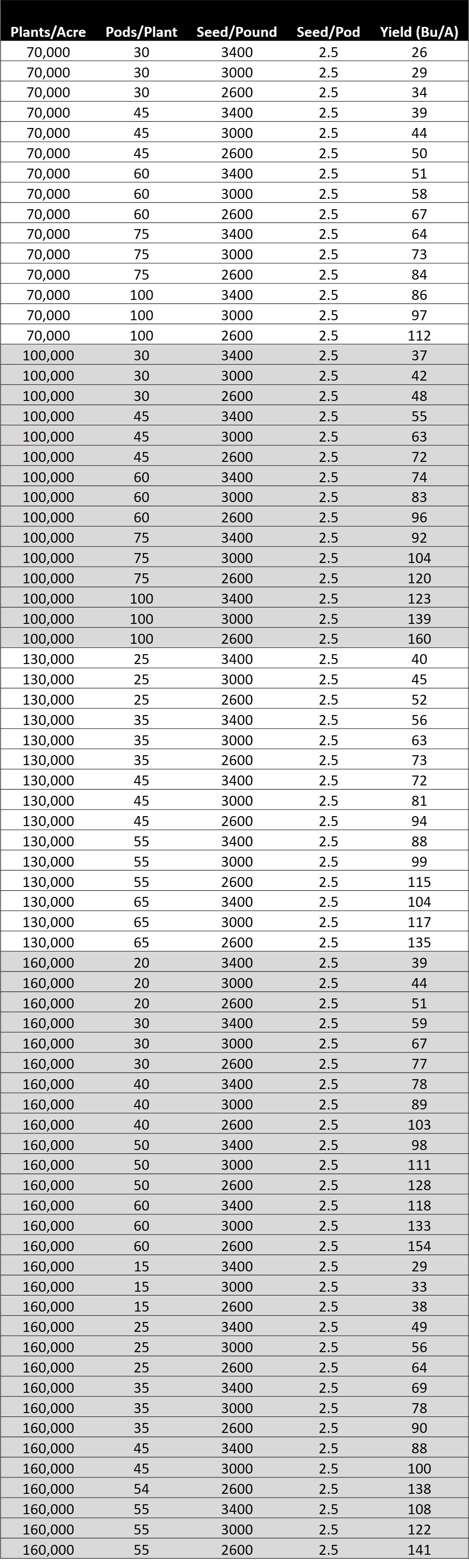

Seeding Rate. Beginning next week in Virginia, plant 140,000 to 160,000 seed/acre and increase that rate by 20,000 seed/acre with each successive week. This will of course put the seeding rate up to 200,000 to 220,00 plants by the first full week of July, sharply decreasing your profit with greater seed costs and lower yields. Again, this is to insure maximum leaf area and node development. Note that as one moves north and west, greater seeding rates may be needed due to the shorter growing season (e.g., northwest Virginia may require a greater seeding rate than southeast Virginia, or North Carolina). If using a drill, I suggest increasing these rates by 10%.

Insure Good Soil-to-Seed Contact. First, adequately spread the wheat residue. No planter will uniformly plant through inches of matted residue. Then make sure the planter is properly set to 1) cut the residue, 2) penetrate the soil to the proper seeding depth, and 3) ensure good soil-to-seed contact. These steps must take place in order. And they affect each other; a mistake in accomplishing one of the steps can result in mistakes in the other two. I suggest waiting until late morning to begin planting to insure that the small grain residue to dry – unless the residue is dry, cutting through it will be a problem, resulting in hair-pinning of the residue and prohibiting proper soil-to-seed contact.

Plant into soil moisture. If there is plenty of moisture, you can plant as shallow as ¾ inch and get good and rapid emergence. If a little dry on top, you can plant as deep as 1.5 inches. With warm soil temperatures, soybean will generally emerge well from this depth and may even emerge from even deeper depths (but I don’t recommend). Unless you farm in wet, poorly drained soils or are growing continuous soybean, I don’t usually recommend a fungicide seed treatment during June and July due to warm soils. Double-crop soybean usually emerge quickly if planted into soil moisture and will “out-grow” any seedling disease.

Insure Nitrogen Fixation. If soybean have not been grown in a field for the past 3 years, then be sure to apply inoculate to the seed with the proper bacteria. This will insure adequate nitrogen fixation by the soybean plant. There is no need to apply nitrogen; definitely don’t apply more than 25-30 pounds/acre or you will inhibit this vital biological process. As a side note, we did find a fairly consistent 1 bushel yield increase with starter N at 25 lbs/acre due to slightly better early-season growth; but this did not pay for the cost of the N – so I don’t recommend.

Fertility (P, K, S, etc.). Keep in mind that the straw contains quite a bit of nutrients. If the straw is harvested, make sure that you are replacing those nutrients that are leaving the field. For more information, see our VCE publication, The Nutrient Value of Straw. And make sure that you are being paid more for the straw than these nutrients and organic matter is worth!