Due to the recent rain, scab risk is increasing in portions of Virginia, especially on the Eastern Shore and coastal areas. The scab risk assessment tool can be found at http://www.wheatscab.psu.edu. Many fields are at or near flowering. In most areas, moderately resistant (MR) varieties are in the low to medium scab risk category, but keep in mind that many acres are still planted to moderately susceptible (MS) or susceptible (S) varieties such as Shirley. In the eastern portions of the state, scab risk is projected to be high for susceptible varieties over the next week, and it will likely be necessary to work in fungicide applications between rain events. Fungicides targeting scab should be applied within 5-6 days of flowering (50% of main tillers starting to flower from the center of the head). Do NOT apply a strobilurin or fungicide pre-mix containing a strobilurin after flag leaf emergence (Feekes 9) since this can increase DON contamination in the grain. Prosaro, Caramba, and Proline are the most effective products for reducing scab and DON contamination. These fungicides will also control foliar diseases such as leaf blotch, stripe and leaf rust, and powdery mildew. Stripe rust has been observed on susceptible wheat cultivars in some fields for several weeks now, but levels remained low due to dry conditions. The recent rain and humid conditions have resulted in spread of the disease in some areas. Similar conditions are forecasted over the next week and the disease has the potential to spread rapidly, so growers should scout their fields immediately to determine if stripe rust is present.

Do You Need To Inoculate Your Soybean?

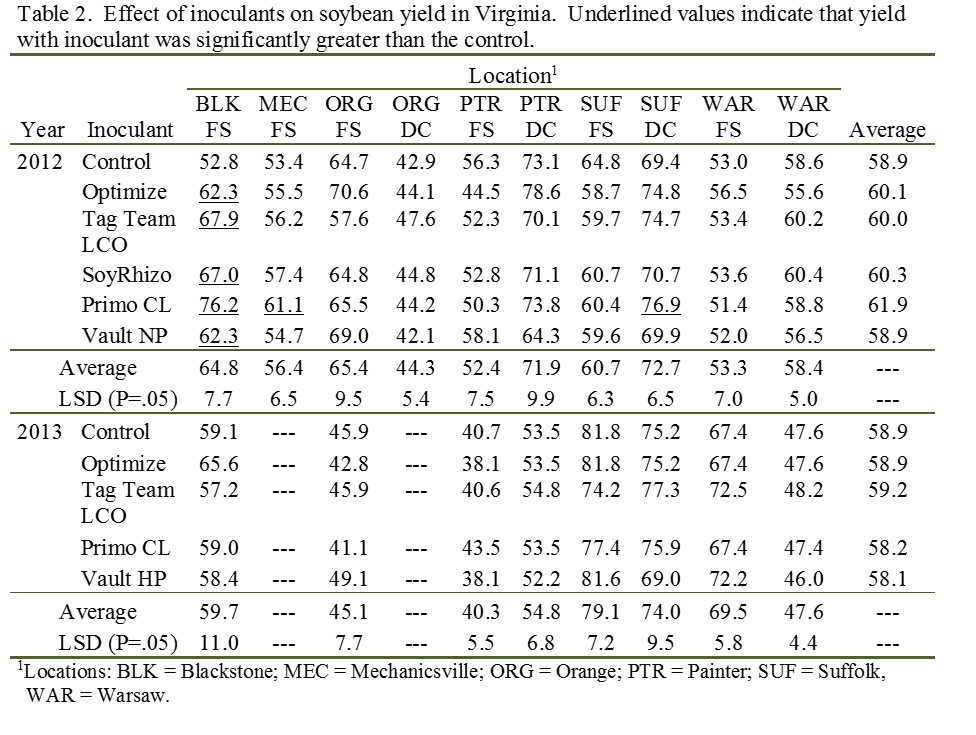

Do soybean inoculants work? Yes. Soybean cannot fix its own nitrogen without the symbiotic relationship formed between the roots and a soil bacteria called Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Soybean inoculant contains this bacteria.

Do you need to inoculate your soybean seed? Maybe. If you’ve never grown soybean in the field that you plan to plant them, definitely add the inoculant to your seed. Or better, inject some liquid into the furrow (you’ll get 3 to 4 times the amount of bacteria). Also, if you don’t have a long history of soybean in the field, inoculate; it will likely pay off.

But what if you are rotating the land to soybean on a regular basis? You are not likely to get a yield response. In a 2-year study on soils that were rotated regularly with soybean, I only found 1 of 18 sites that responded to an inoculant. And the site that responded was land that had only been in production for less than 5 years (formerly pine trees). In all fairness, one inoculant product at one other location (SUF DC, 2012) did yield more than the untreated check.

There are some caveats that I should mention. Sometimes, a yield response if more probable. If you haven’t grown soybean in the last 4 to 5 years, then it may be good insurance. If the field was flooded or if it experienced extreme drought conditions in the previous year, bacteria might have died off; therefore, there is a greater likelihood of a yield response to the inoculant.

There are some caveats that I should mention. Sometimes, a yield response if more probable. If you haven’t grown soybean in the last 4 to 5 years, then it may be good insurance. If the field was flooded or if it experienced extreme drought conditions in the previous year, bacteria might have died off; therefore, there is a greater likelihood of a yield response to the inoculant.

In summary, inoculants do work and they are good insurance treatments. But, they will rarely result in a yield benefit if the field has been regularly rotated to soybean.

If you do decide to use an inoculant, follow the label closely. I prefer to apply the inoculant as close to planting as possible. Note that certain chemical seed treatments (including molybdenum or “Moly”) can injure or kill the bacteria. The less time that these chemicals are in contact with the bacteria, the better.

Should I Plant Soybean in April?

My usually answer to this question is “No…at least not on a big part of your acreage.” But, let’s rephrase the question to “Can you plant soybean in April?” The answer is clearly “Yes, you can…but don’t plant the entire farm in April.” Below, I’ll discuss the reasons for these answers.

What are the advantages to planting in April? One advantage is that the crop mature earlier. A general rule of thumb is that planting 30 days earlier will allow you to harvest about 10 days earlier? Only you can decide if harvesting 10 days earlier is an advantage though. So, ask yourself if this fits into your operation.

You can also gain another 10 or so days by selecting a variety that is at least a full maturity group earlier (e.g., MG 4.5 instead of a 5.5, or a 3.7 instead of a 5.0). You’ve then changed your systems substantially. Such a system is commonly referred to as the Early Soybean Production System (ESPS), which is now the most common soybean production system in the Mid-South/Delta growing region of the country.

But choosing an earlier variety and/or planting early is not just about harvesting earlier. You will also place the most critical time of soybean development (pod and seed fill) earlier in the season. For the Mid-South that regularly experiences drought in August, the ESPS puts those critical stages into July and early August; thereby avoiding the driest (and maybe hottest) time of the year. In addition, this system captures more sunlight per day during the pod and seed development stages (i.e., the days are longer in July than in August which are longer than in September), With more photosynthesis per day during these stages, we can gain yield potential. Early planting was also found to be beneficial in the Midwest; I suspect that the longer days were the primary benefit there. So theoretically, yield potential is greater with early planting of early-maturing varieties, even if drought in August is not the major concern.

Although similar benefits are possible in Virginia, planting early with an early-maturing variety can result in lower yields. Why? First, droughts in Virginia are intermittent. In some years, August is our driest month, in others it is July or June or September or…. Furthermore, most of our soils hold very little water. In some soils, we are 10 days from the last rainfall to a drought. Add to this that the hottest and usually driest time is late-July and early-August, and you have a recipe for disaster with early planting and/or early maturity groups.

But, what if you irrigate? These are the fields that I would use an early soybean production system. A high plant-available water-holding capacity soil also helps. At least you can avoid the drought stress. And because the season is naturally shorter, you will likely spend less on irrigation. But, there is still the heat risk. Only time will tell if the benefits outweigh the risks. Even in irrigated fields, you may only want to dedicate a small portion of your acreage to an early system.

A final risk from planting early is seedling diseases. It may take 2 to 3 weeks for soybean to emerge if planted in April. So, be sure to use a fungicide seed treatment.

In summary, there may be benefits to planting early and/or using earlier-maturing varieties. But, I think that the risks outweigh the benefits, especially in rainfed conditions.

Wheat Disease Update – April 12, 2016

Stripe rust has been found on wheat in southeastern Virginia (Suffolk) and the Eastern Shore (Northampton County). Stripe rust is not observed every year, but it can be more aggressive than leaf rust and spread very quickly if temperatures are moderately warm and humidity/rainfall is high. Many wheat varieties are susceptible, and we do not have good stripe rust ratings for the region because the disease is fairly rare. Pictures showing typical symptoms of leaf rust and stripe rust are below. Fields should be scouted, and keep in mind it is more important to catch stripe rust early than leaf rust. If a field has good yield potential and stripe rust is present, a fungicide application is recommended. In addition to rust, powdery mildew has been reported from throughout Virginia and leaf blotch has been observed in southeastern Virginia, so as the wheat crop approaches the flag leaf emergence growth stage, it is time to start thinking about disease management. For specific fungicide recommendations, see my earlier post (April 7, 2016).

Wheat Disease Update April 7, 2016

As the wheat crop approaches the flag leaf emergence growth stage, it is time to start thinking about disease management. When conditions are conducive to disease development (e.g. high humidity, warm temperatures) foliar fungicide applications may be necessary to protect wheat yield and quality. The mild winter in 2014/2015 resulted in early onset of foliar diseases in some areas, and powdery mildew and rust were reported from a few fields as early as December. Recently, powdery mildew has been reported from throughout Virginia, leaf blotch has been observed in southeastern Virginia, and leaf and stripe rust have been reported just south of Virginia in North Carolina.

Once the flag leaf emerges, this leaf surface, which feeds the developing grain, should be protected from disease if symptoms are observed on the lower leaves and conditions are conducive to disease development. Fungicides containing a strobilurin should not be applied after heading but are a good option for control of foliar diseases as the flag leaf emerges. Late applications of strobilurins can increase DON (vomitoxin) if scab infections occur during flowering. Triazoles including Caramba, Proline, and Prosaro are good options for scab control and will also control late-season foliar disease. Currently, scab risk in the region is low but growers should consult the FHB prediction tool (http://www.wheatscab.psu.edu/) as the crop gets closer to flowering. Ideally, fungicide applications should be made based on scouting and/or risk of infection and disease development due to weather conditions. A fungicide efficacy table for many of the products registered for wheat can be found below.

2016 Wheat Fungicide Efficacy Table

As always, for more information on disease management in field crops feel free to contact Dr. Hillary Mehl, Extension Plant Pathologist by email (hlmehl@vt.edu) or phone (757-657-6450 ext. 423).

APPLIED RESEARCH ON FIELD CROP DISEASE CONTROL 2015

Trial summaries for applied research on field crop disease and nematode control conducted in Virginia in 2015 are now available.

Applied Research on Field Crop Disease Control in Virginia, 2015

Bt-Corn Refuge Requirements for Virginia Counties With and Without Cotton Acreage

Field corn hybrids—what are you buying? The dizzying array of Bt trait combinations available in field corn hybrids makes it important to understand what you are buying in a corn hybrid. Because of the different Bt toxins expressed in the plants, different hybrids protect, or not, against different insect pests. So you should choose your hybrids at least in part based on the history of insect pest pressure in your fields. Good summaries of which hybrids protect against which insect pests are provided in the fact sheets, below (developed by Dr. Chris Difonzo at Michigan State University).

What are Bt-corn refuges and why do we need them? Bt-corn refuges are areas within or near Bt-hybrid planted fields where non-Bt hybrids are planted. They can be either structured (planted as a block or series of rows), or as refuge-in-a-bag (RIB) where the seed is pre-mixed to the correct ratio of Bt and non-Bt hybrids. In Virginia, the refuge requirement is primarily because of the corn earworm. Having the non-Bt corn refuge available in the near vicinity of the Bt hybrids allows at least some corn earworms to not be exposed to the toxins—which should prevent or slow the resistance development process.

Refuge requirements for counties with no cotton! Non-Bt corn refuges are required for corn fields planted to Bt hybrids. These requirements (% of field that must be planted to a non-Bt hybrid or RIB) are different for the different Bt-corn hybrids—and these details are presented in the fact sheet, below, ‘Handy Bt Trait Table’.

Refuge requirements for counties with cotton! Bt-corn refuge requirements are different for areas where cotton is grown because the risk of corn earworm (also called cotton bollworm) developing resistance to the Bt toxins in these areas is greater. Corn earworm attacks both corn and cotton and some of the Bt traits in corn hybrids are also in cotton varieties. Feeding on the same Bt products in both crops exposes corn earworm to the same toxin in successive generations in the same growing season (corn first, then cotton). This increases the risk of the insects developing resistance to the toxins. For Virginia, EPA has designated Dinwiddie, Franklin City, Greensville, Isle of Wight, Northampton, Southampton, Suffolk City, Surry, and Sussex as cotton growing regions. Refuge requirements for the different Bt-corn hybrids are presented in the fact sheet, below, ‘Handy Bt Trait Table for the Southern Cotton-growing Region’.

Abiding by Bt-corn refuge requirements is good stewardship and important for helping sustain the efficacy of Bt-corn hybrids against insect pests. So, to determine your Bt-corn refuge requirement, you need to know if you are planting in a cotton-growing county, and what varieties you plan to plant. Read the attached fact sheets carefully for details to help you select the right corn hybrids for your farm, and what your refuge requirements are.

Peanut “talks”

As we are getting close to a new peanut season, I thought you might want to know in summary what peanut “pointers” in the region and beyond are envisioning for 2016. Here I prepared a compilation of news, comments, and recommendations from the peanut specialists across the country; I included some of my own thoughts as well.

Unanimously, cultivar selection seems to be the most important production decision. Virginia-type cultivars Bailey, Sugg, Sullivan, Wynne, and Emery are recent releases, but registered seed for 2016 production is only available for the first four. They can produce high yields (Bailey in particular) and have good disease resistance package (Sullivan in particular). Bailey and Sugg have normal oil chemistry, and the others are high oleic cultivars. Wynne, Sugg, and Emery have larger kernels than Bailey and Sullivan. Runners can also be successfully grown in Virginia. Georgia-09B, Florida-07, FloRun™ ‘107’, TUFRunner™ ‘297’, and TUFRunner™ ‘511’ are preferred by shellers. I only tested Georgia-09B and Florida-07 in the past, and they both yielded comparable with Georgia-06G and Bailey. I will have an answer about the others for the next year’s planting season.

Speaking about planting, three things were always mentioned at specialist talks: rotation, rotation, and rotation. In Virginia, we are now seeing good yields because of good genetics and rotation; I don’t think we changed other cultural practices by much but could afford longer rotations when acreage dropped. In one out of three or more years peanut should be planted in the same field. Good rotation crops are corn, sorghum, cotton, and small grains, but not soybean. With longer rotations, beneficial Rhizobia bacteria should be provided at planting for optimum nitrogen fixation. Bacteria are living organisms. Handling it with care is what ensures successful inoculation. For us, liquid inoculant applied in furrow on top of the seed worked very well for the past few years. Nitrogen fertilizer seems never to work as well for peanut as an efficient inoculation.

Legumes including peanut are good scavengers of phosphorus and potassium, but require calcium, boron, and manganese, which are deficient in sandy soils preferred by peanut. Calcium and boron deficiencies are difficult to detect until after harvest in the form of “pops” when calcium was insufficient and damaged kernels by “hallow heart” when boron was not enough. Therefore, to ensure sufficient calcium and boron for the growing seed recommendation to apply these nutrients early on in the season, beginning flowering to beginning pegging, is generally accepted by all peanut specialists. Manganese deficiency is easy to see and correct for when it happens. Sulfur might have become needed in peanut production, but timely gypsum application takes care of both, calcium and sulfur. Some specialists talk about zinc toxicity. I personally have not seen one in Virginia, but it does not mean it may not be. Having soil tested every year always helps. Recommendations are to keep soil pH at 6.2 when soil-test zinc is 10 pounds per acre and 6.6 if zinc is 40; but then more manganese is needed.

Protection wise, there were many talks about PPO herbicide and neonicotinoid insecticide resistance, and removal from the market of Tilt Bravo™ because of export concerns. An early tank mix of Alto 100 SL (5.5 oz) and Bravo WeatherStik (1.0 pint) can be used instead of Tilt Bravo™. Velum Total by Bayer has proven good control of thrips in peanut tests in Virginia and North Carolina. Also an improved tank mix version of Provost has become recently available as Provost Opti by Bayer.

The bottom line, 2016 is going to be under El Niño influence, with warm weather in central Pacific; wet and cool fall and winter, dry and warm spring, and dry late summer. Ron Heiniger, corn specialist at the North Carolina State University, thinks 2016 is going to be an excellent year for corn production, but what about peanut? Warm and dry spring, dry late summer, and cool and wet fall? Oh no, not again! Maybe a good option is to get ready to plant early, if indeed the temperature is over 65 °F or better 68 °F; plant Wynne, Sugg, Gregory, and CHAMPS (I know there are still a few growers that grow those) only if irrigation is available; plant at least two cultivars in dryland, Bailey and Sullivan.

The National Weather Service in Wakefield, VA, is organizing a workshop at the Tidewater AREC on March 17. They will provide agriculture-relevant information and invite anyone interested to participate. Their agenda is here National Weather Service Workshop Agenda

2016 Wheat and Growing Degree Day Accumulation

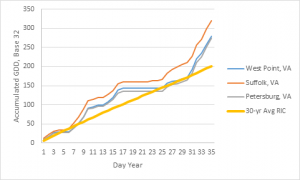

Previous work in VA has demonstrated that we “normally” accumulate around 1350 GDD from planting to jointing in wheat in Virginia. The warm weather this year has been anything but normal and so I don’t think we can follow that guidepost this time.

Our wheat varieties require at least 30 days of temps less than about 42 degrees to vernalize. In most areas we made that threshold of at least 30 days between what I considered to be a normal planting date for the region and the end of the year. For example near Richmond a crop with planting date of Oct 20 would have experienced 31 days with lows below 42F before January 1. Other researchers have reported that wheat requires around 700 GDD after the vernalization threshold has been reached. This seems pretty reasonable for use in VA. When comparing to the 30 year average temperatures for central VA, 700 GDD accumulated from January 1 predicts a jointing date of March 20. I believe this matches well with historical observations for the crop

Below is a figure showing GDD accumulated at 3 sites in eastern VA since January 1, 2016.

Yep – it’s been warm. About 40% greater GDD accumulation at this point in the year compared to the long term average. Normally we are accumulating about 5.75 GDD/day this time year. This year it’s over 8.

I honestly don’t what this means for us in terms of wheat development.

If the temperatures return to the 30 year average tomorrow the warm weather thus far would have relatively little impact. Instead of predicting a jointing date of March 20 (700 GDD) we would get to 700 GDD on about March 15.

The 14-day forecast I’m looking at has us continuing to stay warmer, however.

If we stay near the current trend through jointing, it’s possible we will be 3 weeks ahead of the long term average.

I won’t pretend to be able to forecast the coming weather, but I think it’s likely that things may begin to happen very quickly with the crop.

This may impact our ability to split N applications as driving over wheat that’s already jointed damages the growing point. I suspect weeds, insects, and disease are also responding to these warmer temperatures. Small weeds are going to get to be big weeds sooner this year. Diseases like powdery mildew have already been found in the crop in some places. Scouting early and often may prove a valuable investment.