Corn earworm (=bollworm) moth captures from southeast Virginia black light traps this week were 7 per night at Templeton (Prince George Co.) and 9 per night at Disputanta (Prince George Co.); Suffolk numbers reached 60 per night. Here is the Table. In our pyrethroid resistance monitoring tests, the seasonal average is at 33% survival (n=502 moths tested).

Monitoring Fall armyworm – Week of August 25, 2022

By: Kelly McIntyre and Thomas Kuhar

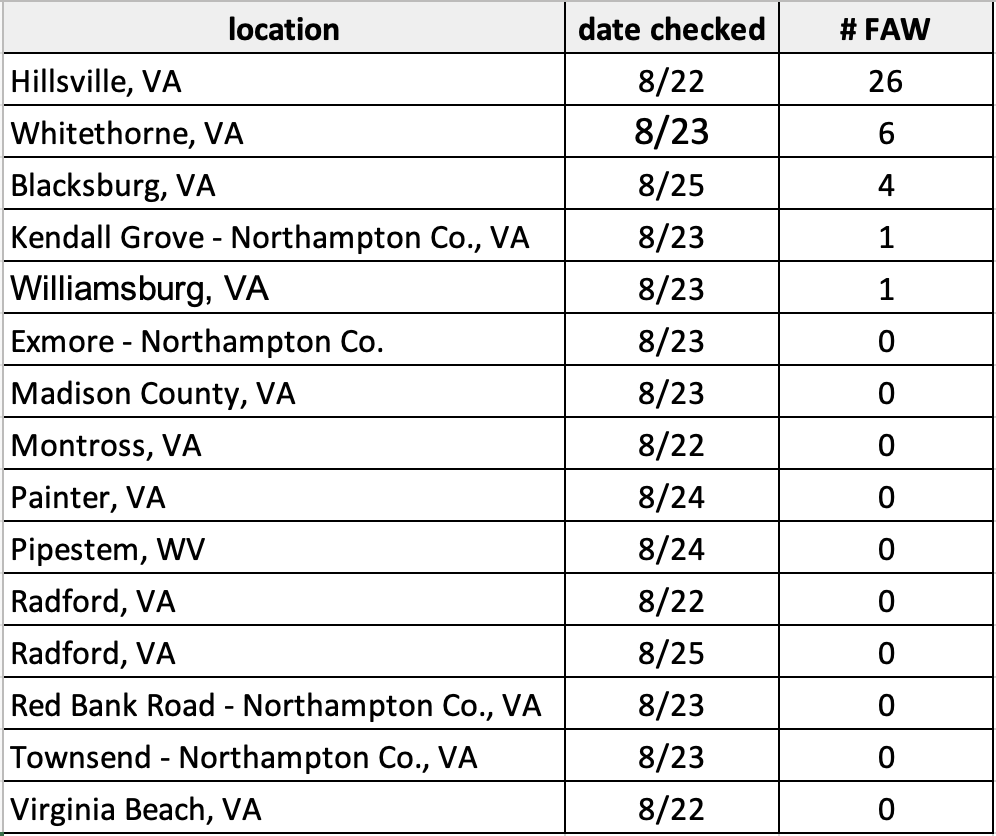

This week FAW adults were observed at 5 of 15 monitoring locations throughout the state. Western regions (Carroll and Montgomery counties) of the state had greater counts (4-26 individuals) though adults were also observed (1 individual) in eastern Virginia (Williamsburg and Northampton County). See table for all locations and counts.

Monitoring Pickleworm and Melonworm – Week of August 25, 2022

By Lorena Lopez, Kelly McIntyre, and Tom Kuhar

Last year, we at Virginia Tech started a pickleworm and melonworm monitoring program consisting of information exchange between cucurbit growers and extension agents across the state that looked for these pests’ damage to cucurbit blossoms or fruits. In 2021, we recorded up to 80% of squash fruits or flower buds infested with either pickleworms or melonworms. This year we continued with the monitoring efforts by monitoring closely summer squash fields in the Eastern Shore, Blacksburg, and Chesapeake area and no pickleworms nor melonworms have been detected.

Additionally, we set up traps with pickleworm pheromone lures in squash and pumpkin fields in Montross, Hillsville, Cape Charles, Painter, Hampton Roads, and Madison County. If these moths are present in the area, they will be attracted to the lure at night when they are active. After two weeks of trapping, no pickleworms or melonworms have been caught in the traps. We will continue to trap these pests as the summer squash season finishes and the pumpkin season continues and will keep you updated.

Corn earworm/bollworm update for August 25, 2022

This week’s corn earworm (=bollworm) moth captures from local black light traps were: Sara Rutherford (Greensville ANR Agent) reported a nightly average of 20 moths; Scott Reiter (Prince George ANR Agent) had 8 per night at Templeton and 10 at Disputanta; the Spiers reported 5 per night in Dinwiddie; and we averaged 28 in Suffolk. Here is the Table. In our pyrethroid resistance monitoring tests, the seasonal average is at 30% survival (n=395 moths tested).

Monitoring Fall armyworm, Pickleworm, and Corn Earworm in Virginia – Week of August 19

By Kelly McIntyre1, Helene Doughty2, Lorena Lopez2, and Tom Kuhar1

This summer and fall, we are tracking moth flight numbers around Virginia using pheromone traps for three important pests, fall armyworm (FAW), which can attack most grasses, corn, sorghum, small grains, and even alfalfa; pickleworm, which is a late season pest of squash, pumpkins, and cucumbers, and corn earworm (CEW), which attacks over 300 host plants including many of the major crops in Virginia. FAW and pickleworm do not overwinter in Virginia and typically are carried northward in late summer on storm fronts coming from the south.

Researchers have demonstrated that certain trap types are better for certain moth species. We are monitoring fall armyworm moths using the bucket trap baited with a Trece FAW pheromone lure and placed near corn fields. We are monitoring the presence of pickleworm moths using the Trece Deltatrap baited with the pheromone lure and placed around pumpkin fields. Corn earworm is monitored using the Heliothis mesh trap or the Hartstack wire mesh trap, which catches the most corn earworm moths among all trap types.

| FW = fall armyworm; PW= pickleworm; CEW = Corn Earworm | ||||||

| name | location | date checked | # days since last check | # FAW (if applicable) | # PW (if applicable) | # CEW (if applicable) |

| Mcintyre | Homefield Farm – Whitethorne | 8/9 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 5 |

| Mcintyre | Wall Farm – Blacksburg | 8/9 | 6 | na | na | 109 |

| Mcintyre | Turfgrass Center – Blacksburg | 8/9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Mcintyre | Homefield Farm – Whitethorne | 8/17 | 8 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Mcintyre | Wall Farm – Blacksburg | 8/17 | 8 | na | na | |

| Mcintyre | Turfgrass Center – Blacksburg | 8/17 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Mcintyre | Homefield Farm – Whitethorne | |||||

| Mcintyre | Wall Farm – Blacksburg | |||||

| Mcintyre | Turfgrass Center – Blacksburg | |||||

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 6/15 | 7 | na | na | 30 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 6/22 | 7 | na | na | 8 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 6/29 | 7 | na | na | 7 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 7/6 | 7 | na | na | 24 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 7/13 | 7 | na | na | 5 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 7/20 | 7 | 0 | na | 18 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 7/27 | 7 | 0 | na | 39 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 8/3 | 7 | 2 | na | 19 |

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 8/12 | 9 | |||

| Doughty | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 8/17 | 5 | 155 | ||

| Romelczyk | Montross | 8/12 | 4 | 0 | ||

| Romelczyk | Montross | 8-17 | 9 | 0 | ||

| Lopez | ESAREC, Painter, VA | 8/18 | 7 | na | 0 | na |

| Flanagan | Cullipher Farms, VB, VA | 8/18 | N/A | 34 | 0 | |

| Lopez | HRAREC | 8/18 | 7 | na | 0 | na |

| Lopez | Sea Breeze Farm, Cape Charles | 8/18 | 7 | na | 0 | 42 |

| Deitch | Arlington RD – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | na | 8 | |

| Deitch | Seaview – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | na | 246 | |

| Deitch | Machipongo – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | na | 43 | |

| Deitch | Nassawadox – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Townsend – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Kendall Grove – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Red Bank Road – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Exmore – Northampton Co. | 8/2 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Arlington RD – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | na | 25 | |

| Deitch | Seaview – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | na | 3 | |

| Deitch | Machipongo – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | na | 66 | |

| Deitch | Nassawadox – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | na | 8 | |

| Deitch | Townsend – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Kendall Grove – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | 1 | na | |

| Deitch | Red Bank Road – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Exmore – Northampton Co. | 8/9 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Arlington RD – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | na | 16 | |

| Deitch | Seaview – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | na | 4 | |

| Deitch | Machipongo – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | na | 168 | |

| Deitch | Nassawadox – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | na | 4 | |

| Deitch | Townsend – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | 1 | na | |

| Deitch | Kendall Grove – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Red Bank Road – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | 0 | na | |

| Deitch | Exmore – Northampton Co. | 8/16 | 7 | 0 | na |

Fall armyworm in southwest Virginia sweet corn – treatment evaluation and recommendations

By Kyle Bekelja (postdoc), Tom Kuhar (Professor), and Sally Taylor (Associate Professor) Department of Entomology, Virginia Tech

We installed our pheromone bucket traps for fall armyworm in late July at Homefield Farm in Whitethorne, VA and we caught moths the first week (8 per trap). This alerted us that this tropical moth pest had already reached southwest Virginia. Then, this week, August 16, 2022, we noticed a pretty bad infestation of FAW larvae in our sweet corn at this same location.

The Pest. Fall armyworm (FAW) is a moth pest that migrates northward during late summer and early fall. Be on the lookout for this pest especially during times of northerly winds (such as tropical storms) which can carry female moths to Virginia late in the season. Fall armyworms have a wider host range that includes more than 80 plants: vegetables include sweet corn, tomatoes, and peppers, field and forage crops such as alfalfa, cotton, and peanuts, and ornamental commodities, especially turfgrass. Last year, FAW hit turfgrass hard in Virginia; this year, we have already started seeing it in sweet corn. Based on observations from Dr. Scott Stewart in Tennessee, we believe that this strain of FAW favors corn and is likely not going to be a huge turf pest like we saw in fall 2021.

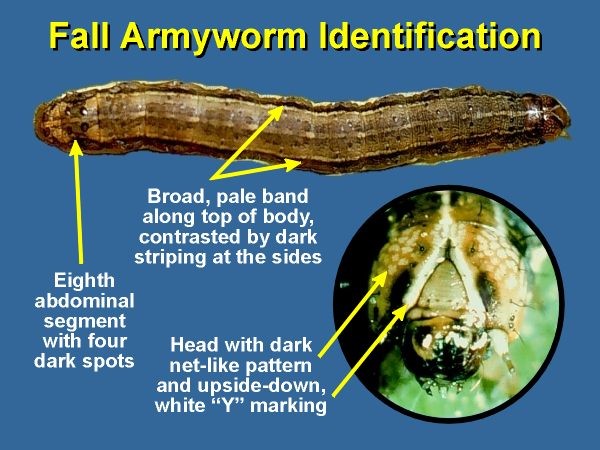

Identification

Be on the lookout for shotgun-patterned damage and lots of frass (i.e., poop) in the corn whorl, shown in Figure 1 (we noticed feeding that was concentrated on un-emerged tassels). If you dig deep inside the whorl, you’re likely to find a caterpillar with the telltale inverted “Y” on its forehead, and four black dots at the tail-end of the abdomen, shown in Figure 2.

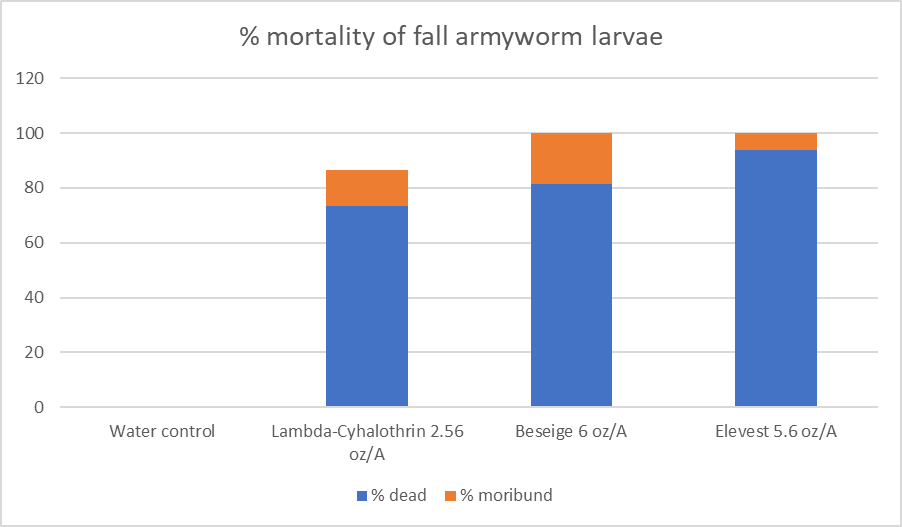

Treatment Evaluation. We collected FAW caterpillars from sweet corn at Homefield Farm in Blacksburg, VA on August 16, 2022, and assessed percent mortality using treatments listed in Table 1. We placed caterpillars in 1-ounce cups with corn tassels that were dipped into solutions of treatments, and assessed mortality after 24-hours. All treatments provided good control compared to a water check. Although the pyrethroid lambda-cyhalothrin resulted in over 83% mortality of FAW, the two products that combine the diamide chlorantraniliprole with pyrethroids (Beseige and Elevest) resulted in 100% mortality after 24 hours.

Insecticide bioassay Results of field-collected fall armyworm larvae.

Control. Insecticides recommended for controlling FAW include pyrethroids (such as Lambda-Cyhalothrin, bifenthrin, and others) and more selective caterpillar-targeting insecticides such as Prevathon, Coragen, and Acelepryn. Consider using some of these more selective options during times when pollinators are more active (e.g., while sweet corn is tasseling). Consult the relevant pest management guides for specific recommendations on various commodities. Remember that control of large caterpillars is often difficult with any insecticide.

Corn earworm/bollworm update for August 11, 2022

This week’s corn earworm (=bollworm) moth captures from local black light traps were: Sara Rutherford (Greensville ANR Agent) reported a nightly average of 13 moths; Scott Reiter (Prince George ANR Agent) had 16 per night at Templeton and 19 at Disputanta; and we averaged 28 in Suffolk. Here is the Table. In our pyrethroid resistance monitoring tests, the seasonal average is at 39% survival (n=278 moths tested).

Be on the lookout for Sclerotinia blight in peanuts.

The system that brought rain on August 10th seems to have broken our streak of hot weather for Virginia’s peanut growing region. Dailey high’s in the 80s with lows in the 60s will continue until August 23rd according to my weather app. The temperature Saturday the 13th may not get above 80o F and the low may be in the upper 50s, which is very favorable for the development of Sclerotinia blight. I anticipate the risk of Sclerotinia blight to be high the next 2 weeks, so fungicide sprays may be warranted in fields with a history of that disease. If growers have sprayed the second spray of Miravis + Elatus fungicides within the past 2 weeks they should be covered. I do not recommend spraying the Miravis + Elatus fungicide tank-mix now if you haven’t sprayed it already due to fungicide resistance concerns with late leaf spot and the lack of curative or “kick back” activity if leaf spot already exists. If the Miravis + Elatus tank-mix has not been sprayed twice already I recommend using Omega 500 at the labeled rates for Sclerotinia blight sooner than later. Typically we recommend growers scout for Sclerotinia blight when the risk of that disease is high according to the Virginia Sclerotinia Blight Advisory. Omega 500 will have greater efficacy if applied prior to or at the initial onset of disease. Follow-up sprays may be made using Omega 500 21 days after the first application if favorable disease weather persists.

As always, if you have questions or concerns about diseases of agronomic crops please feel free to call or text me at (757) 870-8498 or e-mail me at dblangston@vt.edu.

Corn earworm/bollworm update for August 4, 2022

Corn earworm (=bollworm) moth captures continued to increase this week in local black light traps. Sara Rutherford (Greensville ANR Agent) reported a nightly average of 21 moths; Scott Reiter (Prince George ANR Agent) had 11 per night at Templeton and 18 at Disputanta; and we averaged 48 in Suffolk. Here is the Table. In our pyrethroid resistance tests, 45% of moths are surviving the 24-hour pesticide exposure period (n=200 moths tested).

Corn, Peanut and Soybean Disease Update

Corn

Virginia growers are over the hump so far as corn disease management is concerned. Late season diseases such as tar spot and southern corn rust have not been observed in Virginia at this time and we are past the R3 (milk) stage which is the cutoff for making effective fungicide applications for each disease. Click the link for updated maps showing where each disease is currently in the U.S. https://corn.ipmpipe.org/diseases/

Peanuts

As of August 1st, peanut growth and development is a little behind in areas that have experienced periods of severe drought. Heat units for peanuts planted on May 1st so far are on par with 2021, which was a record-breaking year so far as yield is concerned. Growers in Virginia have made at least one fungicide application for leaf spot by August 1st, and many have made 2 applications. The risk of Sclerotinia blight has been variable based on the differences in vine growth due to drought in certain areas, however, recent rainfall events have been more numerous in the region and I expect disease pressure will continue to increase. Increased rainfall and relative humidity will shorten the LESD (last effective spray date) for leaf spot for most fungicide chemistries and growers using Miravis should consider spraying at 21 days after the first application if disease risk for leaf spot is continually high since the last spray of that product. Growers that have already made applications of Miravis tank-mixed with Elatus will have some protection against Sclerotinia blight and growers that are opting for Omega 500 should be scouting fields with histories of that disease, especially in those fields where peanut canopies are dense, to make applications at disease onset. If Miravis or the Miravis/Elatus combo was not applied as the first or second fungicide application I do not recommend using it in August or later due to concerns with fungicide resistance and the lack of curative or “kick back” activity associated with those chemistries. If peanut leaf spot severity becomes high due to weather and the inability to get equipment in fields to make timely fungicide applications, rescue treatments using Microthiol Disperss or chlorothalonil tank-mixed with Group 3 fungicides, such as Provost Silver, to reduce defoliation prior to digging.

Soybean

Fungicides have recently been going out for foliar diseases recently as most soybeans are in the R1 – R5 growth stages. Recent weather patterns have brought and continue to bring rain events and high relative humidity which favor the development of frogeye leaf spot and other foliar diseases. My main concern for fungicide applications is to avoid using Group 11 (strobilurin) fungicide chemistries alone as fungicide resistance to those has been previously documented in the frogeye leaf spot pathogen in Virginia. There are plenty of Group 3 (triazoles), Group 7 (SDHI) and Group 11 fungicide combinations available to manage foliar soybean diseases. Also, I’m thinking of naming August as “SDS (sudden death syndrome) month” as that is when SDS usually starts showing up. The first clinic sample with SDS came in Tuesday on soybeans planted April 15th. Typically, SDS symptoms occur in early planted and early maturing soybeans first and continue as soybeans mature. Soybeans planted early in cool (at or below 60°F), moist soils are more at risk of infection by the pathogen that causes SDS, Fusarium virguliforme. The most visible symptoms occur at the late R5 growth stage and into R6. Managing this disease is strictly preventive through the use of crop rotation, delayed planting, resistant varieties and the fungicide seed treatments ILeVO and Saltro. We are gathering data on SDS outbreaks in Virginia so please contact us if you suspect this disease in your fields.

As always, feel free to contact me if you have questions regarding disease and nematode issues in your fields. e-mail: dblangston@vt.edu, cell: 757-870-8498