Join us next week, November 17th, at the Eastern Shore AREC (33446 Research Drive, Painter, VA, 23420) for Weed Science Specialist Day. Topics will include new herbicide technology and control of herbicide-resistant Italian ryegrass in wheat. The event will begin at 10:00am and conclude at 12:00pm. Lunch will be served promptly following the meeting. Please RSVP to Ursula Deitch (ursula@vt.edu) or Theresa Long (tmjlong@vt.edu) by Friday if you are interested. See the below flyer for more details.

Category Archives: Commodity

Herbicide-resistant Italian Ryegrass

With harvest in full swing, it is hard not to forget about weed control in wheat. Primarily of concern is herbicide-resistant Italian ryegrass. In the past, ACCase- (Hoelon) and ALS-inhibiting (PowerFlex and Osprey) herbicides provided control of this weed. However, Italian ryegrass biotypes resistant to these products have developed, but that is not to say these herbicides will no longer work in your area. For example, Osprey is still effective throughout most of Eastern North Carolina, but once you move into the Piedmont, ryegrass control by Osprey is hit or miss. In areas with known ALS-resistant Italian ryegrass, Zidua is suggested delayed-preemergence. Delayed-preemergence means 80% of germinated wheat seeds have a shoot at least ½-inch long. If applied prior to this stage, injury may occur. Zidua is a seedling-shoot inhibitor and will not control emerged weeds, therefore, it is important for fields to be clean prior to application. Axiom applied spike (applied preemergence, Axiom can cause severe injury) also controls Italian ryegrass if a timely activating rainfall is received following application. Another option on no-till or minimum-till fields (where stubble from previous crop has not been incorporated) is Valor SX applied preplant. Valor must be applied at least 7 days prior to wheat planting and should be applied in combination with either paraquat or glyphosate to control emerged weeds. Tillage should not be performed after Valor SX is applied. Italian ryegrass control by Finesse is variable and growers should expect only suppression. If Finesse is applied, plant only STS-soybean following wheat harvest. Postemergence options for Italian ryegrass include Axial XL and Osprey. Although most Italian ryegrass is Hoelon-resistant, Axial XL (also an ACCase-inhibiting herbicide) still seems to work in most areas. Osprey may also control Italian ryegrass in areas yet to develop resistance and will also control small bluegrass.

More News on Peanut

I attached here two documents. One is the latest JLA update on peanut with information covering Virginia-Carolina region JLA Report_Oct 15. The second is an update by state by Spearman Agency 2015 TS Peanut News.

Virginia Peanut Latest News

In Virginia peanut digging started this year two weeks earlier than in most years, on Sep 15 in most counties. This is because of the combination of genetics, early maturing cultivars, and weather. One may say this summer was dry. Indeed, it was and some fields were more affected by drought than others. But it was a certain type of drought: cool and wet alternating with warm and dry long periods of time. For example, May was warm and dry, and suitable for early flowering; June and half of July were cooler and moist; perfect for peg and pod growth. And that was it: one huge, uniform crop set early on in the season and not two crops like we usually see in dry years. Altogether, by mid Sep the 2600 accumulated heat units were sufficient for Bailey and Sugg, the mostly grown cultivars in Virginia this year, to mature.

Over 85% of the peanuts in Virginia have been dug and in most part picked by now. Yields of those picked before Joaquin and dug after the storm are in 4,000 lb/ac yield and grades are good. Peanuts dug right prior to Joaquin are in good shape, but a lot of pod shedding occurred and this will reduce yield. The peanuts dug a week ahead of storm are in poor shape and some segregation 2 peanuts with a high content of damaged kernels was sold. No segregation 3 was yet reported. A lot of sprouting was also observed.

Murphy Brown is buying sprouted sorghum

Some good news on the sprouted sorghum: Murphy Brown is taking all sorghum (sprouted or not). They will be feeding sprouted grain immediately. They will be paying for sprouted grain based on test weight. Same discounts apply as with non-sprouted grain (source: Barney Bernstein, Entira). I was also informed that on Eastern Shore the Coastal Commodities local elevator is applying a $.50/bu discount for sprouted sorghum, but they are taking it, too. http://www.coastalcommodities.com/

Soybean Seed Quality Continues to Deteriorate

The warm and wet September combined with early planting of early-maturing varieties have led to some rather severe seed quality problems in soybean this year. Our harvest to date indicates that seed quality in our Northern Piedmont is pretty good, but declines as one moves south. There also seems to be a good correlation with lack of rotation, earlier maturity groups, and earlier planting showing most of the problems. The issues can usually be attributed to the diseases phomopsis seed decay and purple seed stain, which I’ll describe in more detail below. Other diseases such as Alternaria, anthracnose, and frogeye leaf spot can also cause seed discoloration and quality issues, but are less common. The bottom of the plant usually has more seed decay than the top. But if harvest is delayed, the entire plant will be infected.

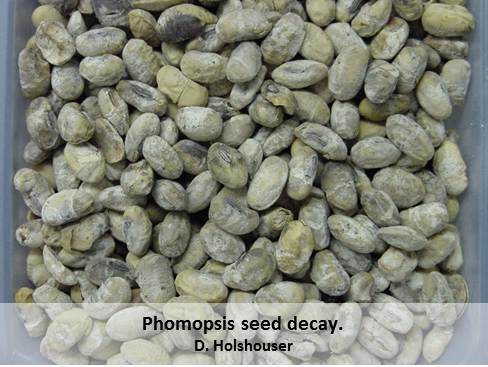

Phomopsis Seed Decay. When soybeans mature during warm and wet conditions, we can expect seed quality to deteriorate. Because this disease develops more rapidly on plants that are maturing under warm and wet conditions, we usually have more problems with early-maturing varieties. We can however have seed decay on our later- maturing varieties if October is warm. Although pods can be infected earlier, seed decay does not usually begin until after physiological maturity (R7).

Infected seed are shriveled, elongated, and c racked. Severely infected seed may appear white and chalky. The fungus secretes enzymes that degrade the seed coat proteins. Test weight can be lower. High occurrence of these seed can lead to discounts or rejection.

racked. Severely infected seed may appear white and chalky. The fungus secretes enzymes that degrade the seed coat proteins. Test weight can be lower. High occurrence of these seed can lead to discounts or rejection.

There are a few things that can be done to reduce the disease incidence. It resides in the soil and on infected residue. So, rotation is very important. More decay will occur in a crop deficient in potassium, infected with viruses, and heavily attacked by insects. Later-maturing varieties and later planting dates that delay maturity into the cooler parts of the year will reduce the incidence. Still, timely harvest is the best management strategy. The longer you leave the soybeans in the field, the worse the disease. So, only plant as many early varieties as you can harvest in a timely manner. Foliar fungicides will decrease the incidence of seed decay if applied from pod development (R3-R4) to early seed filling stages (R5). My experience is that a single R3 will do little to prevent seed decay; it will usually take a second application at R5.

Purple Seed Stain. Purple seed stain is caused by the organism Cercospora kikuchii, the same organism that causes Cercospora blight. Before maturity, fields with Cercospora blight can be recognized by reddish leaves and reddish purple blotches on the stem and leaf petioles. When severe, defoliation of the upper leaves of the plant will take place. In many cases, the blotching progressed up the stem and to the pods.  Dark, nearly black pods may appear on some varieties. Once it progresses to the pods, there is a higher likelihood that the seed will be stained.

Dark, nearly black pods may appear on some varieties. Once it progresses to the pods, there is a higher likelihood that the seed will be stained.

Purple seed stain is very noticeable. The seed will contain pink to pale purple to dark purple splotches, which can cover the entire seed coat. The purple stain itself does not reduce yield, but seed with nearly 100% discoloration may be lower in oil and higher in protein. A lot of staining can result in discounts. Germination of seed with 50% or more staining will likely be delayed.

Usually, the disease first appears on the plant during early seed development. If conditions are right (average temperatures over 80o for several days), then the disease will build up rapidly. Other weather factors do not generally affect seed  infection. Severity of the infection is largely related to amount of infected leaf debris and residue. Therefore, rotation with a non-legume crop is critical for control.

infection. Severity of the infection is largely related to amount of infected leaf debris and residue. Therefore, rotation with a non-legume crop is critical for control.

Other control measures include variety selection, planting high quality seed free of visual staining, and fungicides. Varieties differ in their susceptibility of Cercospora kikuchii, but that information is rarely available in seed catalogs. We routinely evaluate purple seed stain in our variety tests. Fungicides will give some control if applied during pod or seed formation.

Stop peanut digging until frost potential passes

Due to the frost and freeze advisories in effect from Sunday through Tuesday night (Oct 19 through Oct 21) in the V-C region, I recommend that peanut digging be stopped after today (Thu, Oct 15). Peanuts will need three days to dry in order to not be affected by frost. Resume digging only after temperatures become milder.

Frost advisory is available at http://webipm.ento.vt.edu/cgi-bin/listfrost

Virginia Frost Advisory

The Virginia Frost Advisory predicts that a frost is expected next Monday morning (10/19) for Suffolk, Capron, Waverly, Skippers, and Lewiston. A copy of the report can be downloaded below. For up-to-date frost advisories for the region, see the Peanut-Cotton Infonet (http://webipm.ento.vt.edu/cgi-bin/listfrost).

Wet Conditions May Lead to Soybean Seed Sprouting

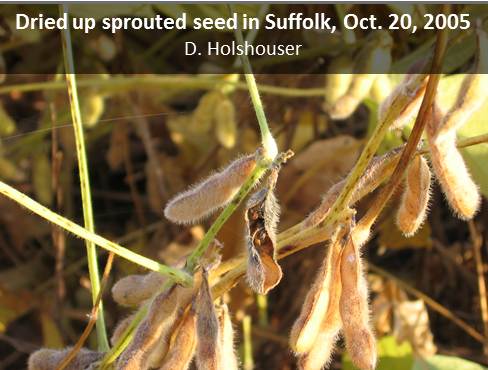

One of the most disturbing late-season issues can be pod splitting and/or seed sprouting in the pod. Pod splitting is most common when pods develop and seed begin to grown (R4 to R6 stages) during dry conditions and seed finish filling under wet conditions. Sound familiar. This is more-or-less what we experienced this year. Seed sprouting is usually caused by extremely wet conditions after the crop is mature and seed moisture has dropped below 50%.

What causes pod splitting? The reason is not clear, but  here are my observations. Generally pod splitting happens when the crop is under severe stress, usually drought conditions up until the full-seed stage (R6). Pods are generally small due to the drought. Then rains set in between R6 (full seed) and R7 (physiological maturity). The seed grow and grow, and seem to outgrow the pods, causing them to split. Obviously, this splitting can then lead to seed quality issues. It can also open the plant up to seed sprouting,

here are my observations. Generally pod splitting happens when the crop is under severe stress, usually drought conditions up until the full-seed stage (R6). Pods are generally small due to the drought. Then rains set in between R6 (full seed) and R7 (physiological maturity). The seed grow and grow, and seem to outgrow the pods, causing them to split. Obviously, this splitting can then lead to seed quality issues. It can also open the plant up to seed sprouting,

Even if the crop does not experience the above conditions and pods do not split due to rapid seed enlargement, wet conditions after the crop is mature can lead to sprouting seed. Sprouting seed is not always directly related to the pod splitting; pods may not split until seed sprout. I’ve seen up to 30% of pods with sprouted seed when conditions are perfect for this. Although an unusual occurrence, seed sprouting can occur if soybean seed drop below 50% moisture, then increase to 50% or more moisture.

In addition, I have seen more sprouting in pods showing Cercospora blight (very dark pods). I do not understand why and could not definitively relate the sprouting to this disease. But, there appeared to be a relationship. Sprouting occurred primarily at the top of the plant where the dark pods were located. In contrast when pods were not dark, I have observed most sprouting at the bottom of the plant where the relative humidity is greater.

Usually, the number of split pods and sprouting seed is low and yield and seed quality effects are minimal. After a week of drying conditions, the sprouted seed will dry up and ma y fall out of the pods. At the worst, there could be some lower test weight and seed could contain more foreign material (from the dried up sprouts). However, the light seed will likely be blown out the back of the combine. If you do observe the problem and it is severe, I suggest that the air on the combine be adjusted to remove those light, sprouted seed at harvest. Too many sprouted seed in the bin could lead to rejection by the buyer.

y fall out of the pods. At the worst, there could be some lower test weight and seed could contain more foreign material (from the dried up sprouts). However, the light seed will likely be blown out the back of the combine. If you do observe the problem and it is severe, I suggest that the air on the combine be adjusted to remove those light, sprouted seed at harvest. Too many sprouted seed in the bin could lead to rejection by the buyer.

Wheat seeding rate and drill calibration, 2015-16

Based on previous research we know we need at least 70-80 heads per square foot to reach optimum wheat yields. That typically requires a seeding rate of 30-35 seeds per square foot, which is equivalent to 20-22 seeds per foot of row in 7.5 inch rows. The reason we advise seeding based on actual number of seeds per seed lot, and not on a pound per acre basis is that seed size varies considerably among wheat varieties and over years for the same variety. The number of seeds per pound is determined both by genetics and by environment. A few of the entries in our state wheat variety test are listed below and it’s obvious that a range of 30% or larger exists among varieties within a year. The consequence of not calibrating grain drills to deliver the optimum seeding rate can vary. If too little seed is planted, yield potential may be compromised. Overseeding increases seeding cost and in a year with smaller profit margins in wheat, we certainly need to avoid both. This management activity is an investment of time, but spending that time can result in greater profit.

|

2016 |

2015 |

2014 |

Mean |

% Dev. |

|

|

———–seed/lb———– |

|||||

| Massey |

13046 |

12371 |

10318 |

11912 |

23% |

| Jamestown |

13472 |

14277 |

11762 |

13170 |

19% |

| Shirley |

11100 |

10861 |

9722 |

10561 |

13% |

| Pioneer Brand 26R20 |

12825 |

14157 |

11378 |

12787 |

22% |

| Pioneer Brand 25R32 |

13593 |

13488 |

13353 |

13478 |

2% |

| Featherstone 73 |

14099 |

12304 |

11436 |

12613 |

21% |

| VA10W-119 |

10993 |

11756 |

9578 |

10775 |

20% |

| Pioneer Brand 26R10 |

10509 |

12587 |

11073 |

11390 |

18% |

| Pioneer Brand 26R41 |

11979 |

10682 |

10913 |

11192 |

12% |

| Pioneer Brand 26R53 |

11671 |

11988 |

11947 |

11869 |

3% |

| Avg. by year | 12329 | 12447 | 11148 | 11975 | |