Hurricane Irene roared along the Virginia coast with high winds and significant rainfall. The rainfall was needed, desperately needed for some parts of the Commonwealth. On the other hand, the high winds caused considerable lodging to the best looking of Virginia’s crop and this lodging will likely lower yield potential. But, because the damage to soybean was not as severe as other crops such and corn, cotton, or tobacco, Virginia’s soybean crop may, in the end, benefit from the storm.

Hurricane Irene roared along the Virginia coast with high winds and significant rainfall. The rainfall was needed, desperately needed for some parts of the Commonwealth. On the other hand, the high winds caused considerable lodging to the best looking of Virginia’s crop and this lodging will likely lower yield potential. But, because the damage to soybean was not as severe as other crops such and corn, cotton, or tobacco, Virginia’s soybean crop may, in the end, benefit from the storm.

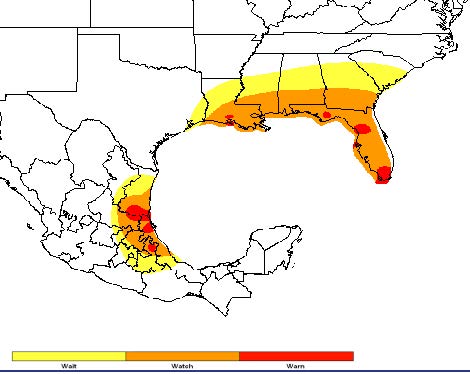

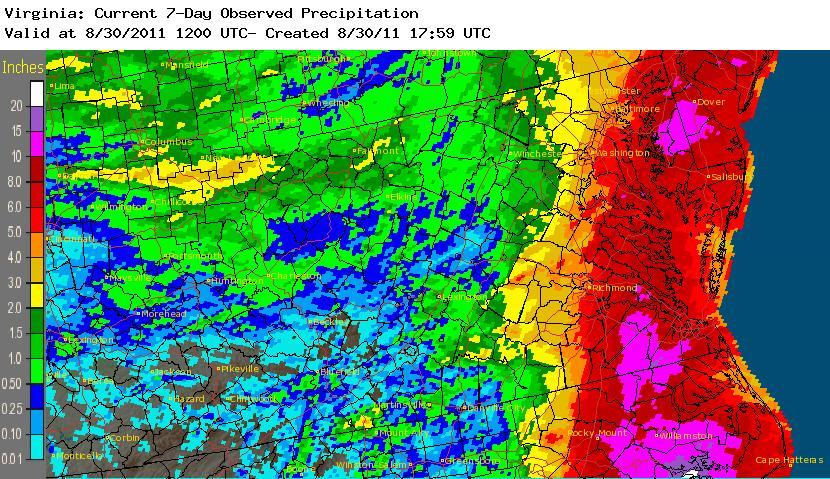

Below are the National Weather Service’s average estimates of rainfall received from Hurricane Irene (you can obtain these maps from http://water.weather.gov/precip/). The greatest amounts occurred in eastern Virginia, but most of our soybean growing regions received rain. Ironically, the hurricane might have saved the soybean crop on the Eastern Shore, which was very dry. The rain comes at a very critical time for this year’s crop. It will insure that pods and seed continue to fill and not abort due to moisture stress. In most areas, the soil profile should be full; therefore, adequate soil moisture should be available to take us as least to the beginning of the R6 (full-seed, seed meeting each other in the pod) stage. I am not however implying that the crop is made. At the beginning of R6, only 50% of the yield is made. But, cooler temperatures and a few more timely rains should insure good yields.

in eastern Virginia, but most of our soybean growing regions received rain. Ironically, the hurricane might have saved the soybean crop on the Eastern Shore, which was very dry. The rain comes at a very critical time for this year’s crop. It will insure that pods and seed continue to fill and not abort due to moisture stress. In most areas, the soil profile should be full; therefore, adequate soil moisture should be available to take us as least to the beginning of the R6 (full-seed, seed meeting each other in the pod) stage. I am not however implying that the crop is made. At the beginning of R6, only 50% of the yield is made. But, cooler temperatures and a few more timely rains should insure good yields.

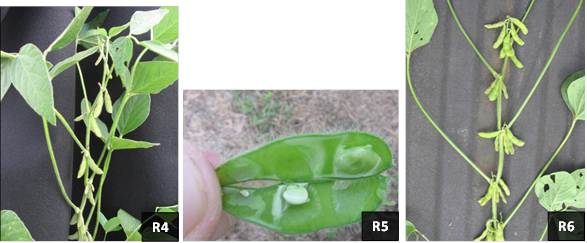

Now for the down side of the hurricane – lodging. How much will the lodging from the hurricane cost us in yield? This will depend on the degree of lodging and the stage that the soybeans were in. In general, I’d say that our full-season crop is in the R5 (beginning seed) to R6 (full seed) and the double-crop soybeans are somewhere between R4 (late pod) and R5. Yield is most severely affected when the lodging occurs at the R5 (beginning seed) development stage. Although yield is still affected at R6, yield losses are only half as severe at this stage. Many double-crop soybeans are only in the R4 stage throughout the state. Yield losses due to lodging at this stage is probably not as great as if the crop was in R5, but could greater than if the crop was in R6 (assuming the same degree of lodging). Still, double-cropped soybeans are usually much shorter and do not have the severe lodging that the more full-canopied full-season crop has. In general, I’d expect less yield loss for the late-planted crop.

So, what’s my estimate on the amount of loss that we’ll incur? First, we have to distinguish harvest or traffic loss from physiological yield loss. Harvest losses can vary anywhere from 3-10% depending on many factors. In some cases, we may have to run the combine of the most severely lodged soybeans in one direction. But, with that said, I expect the soybeans to stand up quite a bit as soon as leaves begin falling. I’ve even seen some recovery only after a few days.

Similar to harvest losses, if we have to drive over the lodged soybean for a late insecticide or another spray, we can see some loss due to running over soybean. We have data from running over R4 stage soybean to make a fungicide application. Depending on the size of the sprayer (larger boom widths cause less loss) and row spacing (7.5-inch soybean yield losses were less than 15-inch soybean), losses ranged from 1 to 4%. Hopefully, we won’t need another insecticide spray.

There is little data on physiological yield loss, but what’s out there seems to be pretty consistent. What do I mean by physiological yield loss? That’s the loss in yield from lodging if all of the soybeans that are now on the plant can be harvested. In controlled studies where researchers simulated lodging and compared it to a crop that was artificially supported, losses have ranged from 0% to over 30%. Why such a range in yield loss? It depends on the severity of lodging and the stage of development in which the lodging occurred.

Let’s first address the severity of lodging. Soybean researchers have traditionally rated lodging on a scale of 1 to 5 as follows:

1.0 = almost all plants erect

2.0 = either all plants leaning slightly, or a few plants down

3.0 = either all plants leaning moderately (45O angle), or 25-50% down

4.0 = either all plants leaning considerably, or 50-80% down

5.0 = all plants down

As you may expect, a rating of 4.0 to 5.0 is very severe lodging. I have seen this in a couple of locations, but at this time I’d rate most of the lodging between 2.0 and 4.0. Yield loss will be minimal unless most plants are leaning at a 45O angle or more. Otherwise, yield losses can range from 10-35%, depending on the stage in which the lodging occurred.

Why does lodging cause yield loss? It’s not completely clear, but the generally accepted reason is a reduction in net photosynthesis. With less photosynthesis, there is less energy going to the developing pods and seeds. When plants are lodged, relatively less of the upper leaves and more of the lower leaves are exposed to sunlight. The upper leaves are more photosynthetically active and the lower leaves are less active. When lodging occurs, the entire energy-producing mechanism is disturbed. In other words, we are now exposing less of the most productive leaves and more of the least productive leaves to the sun. So, yield will decline.

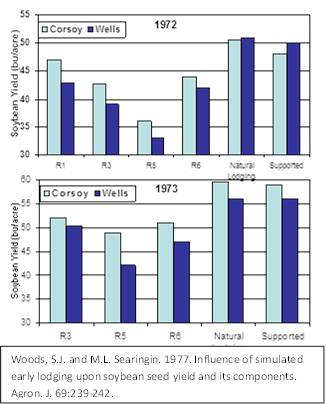

Let’s assume that lodging rated above 3.0 will cause a 10-30% loss. Now the severity of the yield loss will depend on the development stage that the soybean plant was in. As I said earlier, there’s little hard data on this subject, but a few older experiments give us some information. In a study conducted in 1972-73, S.J. Woods and M.L. Swearingin of Purdue University indicated that the R5 stage was the most critical time for lodging to occur. At this stage, yield was reduced by 18-32%. At stages R3 and R6, yield was reduced by  12-18% and 13-15%, respectively. Details of that experiment are shown to the right.

12-18% and 13-15%, respectively. Details of that experiment are shown to the right.

In that study, the plots were manually lodged with a long aluminum bar at the indicated soybean stage. Although lodging ratings were not given, I would consider it to be in the 3.5 to 4.0 range from the description given. Two varieties were tested. ‘Corsoy’ was more susceptible to lodging, but was able to branch more; therefore, it yielded higher when lodged. ‘Wells’ is more resistant to lodging, but did not branch as much; therefore, was unable to compensate as much for the lodging. In the natural lodged plots, only slight (2.0 or less) lodging occurred.

From the above data and a few other studies, I’d estimate that where we had moderate to severe lodging and the soybean were in the R4 or R6 stage, we’ll probably lower our yield potential by 10-15%. If the plants were in the R5 stage and lodging was severe, then losses could be 15-25%. But, most of our lodging was not likely as severe as in the study. In general double-cropped soybeans are not as lodged due to their smaller height, therefore will not suffer as much damage.

One more thing must be mentioned. If soybeans were in even later stages (mid-R6), then yield loss will be less. Our full-season maturity group 3 soybeans planted in mid-May are getting close to physiological maturity (R7, one pod reaching its final brown color) and some early-maturing group 4 soybeans are well into the R6 stage. Once a plant reaches physiological maturity, 100% of the dry matter has accumulated; so there will be no yield loss. Plus, the plants with fewer leaves lodged less.

One more thing must be mentioned. If soybeans were in even later stages (mid-R6), then yield loss will be less. Our full-season maturity group 3 soybeans planted in mid-May are getting close to physiological maturity (R7, one pod reaching its final brown color) and some early-maturing group 4 soybeans are well into the R6 stage. Once a plant reaches physiological maturity, 100% of the dry matter has accumulated; so there will be no yield loss. Plus, the plants with fewer leaves lodged less.

In summary, there will be some loss in yield potential due to Hurricane Irene. I must stress that this is loss in yield potential, which is the yield that soybeans would have made after receiving the rain from Irene, but not the wind that caused lodging. In dry spots or in places that were becoming dry, the hurricane likely benefitted the soybean crop more than it hurt. Overall, average yields may now be greater than before Irene.