Soybean, being a high protein crop, require more nitrogen than any other nutrient. Fortunately, through a symbiotic relationship with soil bacteria, soybean is able to fix its own nitrogen. You can easily see this relationship with bacteria by examining the roots for nodules. If there are plenty of nodules and they are pink inside, the nitrogen-fixing process is working and no nitrogen needs to be applied to soybean. However, if nodules do not form, you could end up with a field similar to the one shown on the right. Below are what the roots looked like.

To insure that you have enough nitrogen for your soybean, you can use an inoculant containing the soil bacteria Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Do soybean inoculants work? Yes. As long as the bacteria is still alive when you put it in the soil.

for your soybean, you can use an inoculant containing the soil bacteria Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Do soybean inoculants work? Yes. As long as the bacteria is still alive when you put it in the soil.

Do you need to inoculate your soybean seed? Maybe. If you’ve never grown soybean in the field that you plan to plant them, definitely add the inoculant to your seed. Or better, inject a liquid inoculant into the furrow (you’ll get 3 to 4 times the amount of bacteria). Also, if you don’t have a long history of soybean in the field, inoculate; it will likely pay off.

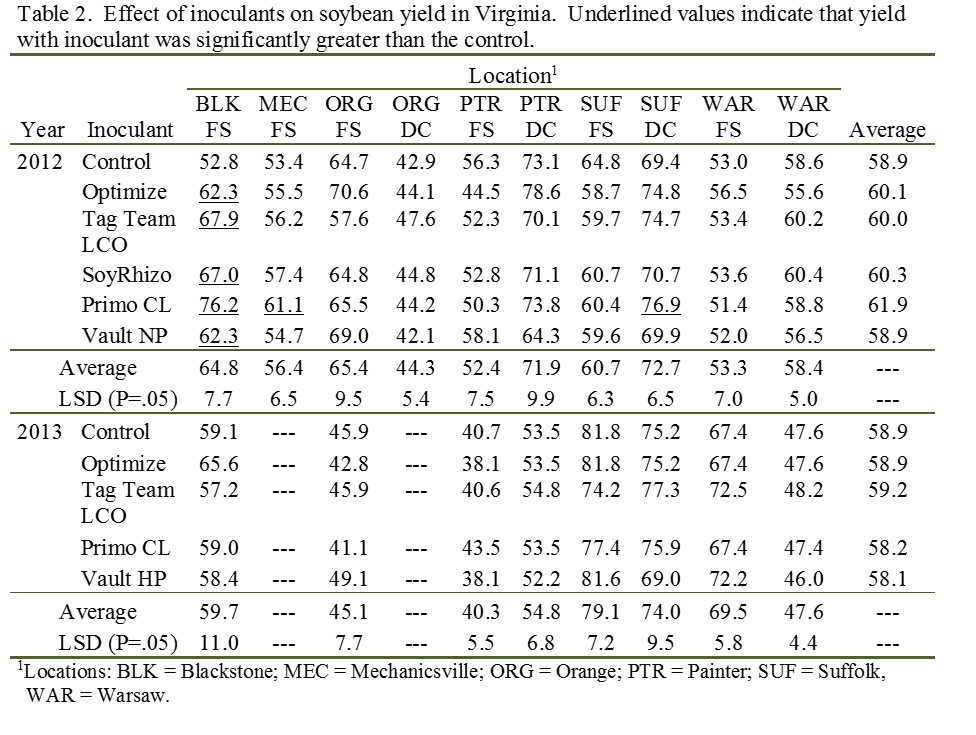

But what if you are rotating the land to soybean on a regular basis? You are not likely to get a yield response. In a 2-year study on soils that were rotated regularly with soybean, I only found 1 of 18 sites that responded to an inoculant. And the site that responded was land that had only been in production for less than 5 years (formerly pine trees). In all fairness, one inoculant product at one other location (SUF DC, 2012) did yield more than the untreated check.

There are some caveats that I should mention. Sometimes, a yield response if more probable. If you haven’t grown soybean in the last 4 to 5 years, then it may be good insurance. If the field was flooded or if it experienced extreme drought conditions in the previous year, bacteria might have died off; therefore, there is a greater likelihood of a yield response to the inoculant.

There are some caveats that I should mention. Sometimes, a yield response if more probable. If you haven’t grown soybean in the last 4 to 5 years, then it may be good insurance. If the field was flooded or if it experienced extreme drought conditions in the previous year, bacteria might have died off; therefore, there is a greater likelihood of a yield response to the inoculant.

In summary, inoculants do work and they are good insurance treatments. But, they will rarely result in a yield benefit if the field has been regularly rotated to soybean.

If you do decide to use an inoculant, follow the label closely. I prefer to apply the inoculant as close to planting as possible. Note that certain chemical seed treatments (including molybdenum or “Moly”) can injure or kill the bacteria. The less time that these chemicals are in contact with the bacteria, the better.